About this testimony: This is a story of manipulation, coercion, and the long shadow of abuse – but it is not based on hearsay. I have reviewed extensive primary material to support Mo’s account. She shared with me dozens of text messages and correspondence shared with the individual mentioned here during and after their entanglement – many of them long, anguished, and unanswered. While the contact details are redacted in the story below, she has preserved the full records.

Mo also gave me access to her private journal entries from that season in her life, capturing her emotional state in real time as the events unfolded. In addition, I spoke to several people Mo confided in at the time, whose testimonies helped corroborate her version of events. The story that emerges is not constructed only in Mo’s personal recollection or hindsight – it is grounded in contemporaneous records, direct messages, and consistent witness accounts.

Peter Ayiro was given a chance to respond to the allegations outlined below. He did not get back to us by the time we were publishing this story.

This is Part II of a two-part investigation. There is important institutional context outlined in Part I, which would be important to appreciate before reading Mo’s story.

~ Christine Mungai

***

Mo Mwangi was a bubbly, expressive child – always singing and learning little dance routines, the kind of child who’s brought out to entertain visitors with an impression of a TV presenter.

Even today, when she speaks, her voice has the rhythm of someone who knows how to paint their words. It’s like her words change font depending on what we’re speaking about – sometimes I hear a Tahoma in her voice, sometimes a Comic Sans. And when she laughs, it sounds like actual peals of laughter – sparkly and shimmering.

Growing up, she went to public schools a walking distance from home, and lived what she describes as a simple, idyllic childhood. Holidays were spent in shags with her Cucu, helping with lighting the fire, or peeling vegetables, or running the endless errands that old people always seem to have.

When she arrived at Alliance Girls High School (the school is nicknamed “Bush”) in early 2014, she was coming with the inner assurance of a gifted child who knew that she was academically bright, but also talented in many other ways that could make people smile. But even that didn’t protect her from the jarring experience that almost all new students report – especially those from outside Nairobi. Like many girls arriving at such a hallowed institution, she felt a little smaller than she was used to.

“We [were] all very smart and intelligent here. It took a while for me to feel like I could take up space. I didn’t come in with the same kind of energy that some of my friends – especially the ones from Nairobi – had. They were just confident from the get-go.”

In Form 1, she auditioned for, and performed in, the inter-house music and drama competitions, two big annual events where students from the different houses – dorms – would compete in the performing arts, sometimes complete with original music and plays written by the students themselves.

There were several older students she recognised from her primary schools back home. One of them had previously been her schoolmate and was now in Form 4 while she was in Form 1. This girl noticed Mo’s enthusiasm for music and especially drama, and quietly called her aside.

“Stay away from Peter Ayiro,” this girl told Mo, and walked away. I have corroborated this account in a separate interview with the girl in question here.

Mo remembers being struck by that moment, especially that this fourth former didn’t call him “Mr. Ayiro” or “Teacher”. But she also didn’t really think this older girl’s information could be trusted.

“I think at 14, I didn’t have the capacity to separate things, you know? Because I’m seeing [this girl]—she sags her tie. And then she’s telling me to be careful... I’m struggling with that. I thought, ‘You run with the wrong crew, you’re around people who get in trouble with teachers.’ So I felt like I couldn’t trust this information.”

Mo joined the drama club and quickly rose through the ranks, getting more prominent roles as she got older. She also became active in the school’s Christian Union (C.U.). Peter Ayiro was the patron of both the drama club and the Christian Union.

“I came from a place where I went to Sunday school, I went to church. I just wanted to continue that same rhythm. I came to high school really wanting to learn about God, to know about God. Believing this girl would have taken me in a direction I didn’t want to go. Because it felt like [Mr. Ayiro] was the point of connection to God. This is the C.U. patron. I didn’t want to stop going to C.U. because of this information.”

And so, she stayed, both in the drama club and in the C.U. With time, she got more responsibilities in both clubs, and by the time she was in fourth form, she was the chairlady of the drama club and of the C.U., and was the entertainment prefect (“Captain” in AGHS parlance) as well.

It was a little unusual, even within Bush’s dynamic school culture, for one student to be both the Entertainment Captain and the C.U. chairlady. These roles traditionally sat on opposite ends of the school’s social spectrum. The Entertainment Captain was usually one of the “cool kids” – the girl who organised concerts, movie nights, and fun days, someone seen as outgoing, social, and a bit edgy. The C.U. Chair, on the other hand, was typically viewed as a “holy Joe” – spiritually mature, upright, often conservative, and often respected for her moral authority rather than her popularity.

But by the early 2010s, Kenyan youth culture was undergoing a shift. Urban gospel music had broken into the mainstream, blending the aesthetic of pop culture with messages of Christian faith. Artists like Juliani, Eko Dydda, Bahati, and a whole host of other musicians were topping the charts and packing concerts with teenagers who saw no contradiction between faith and fun. In that context, the lines between the “cool” and the “holy” began to blur, and so did the roles that students could hold.

Still, for a C.U. chairlady to also hold the entertainment docket was rare – and telling. It wasn’t just about changing trends; it was also perhaps a testament to Peter Ayiro’s influence on the school’s spiritual and social life. As the long-standing C.U. patron and a man deeply involved in youth ministry beyond Bush, Mr. Ayiro was shaping what spiritual leadership looked like. Under his watch, ex-students report that the C.U. became more dynamic and wide-reaching, and his protégés often emerged as influential figures in school life – sometimes even in unexpected spaces like entertainment.

That kind of duality, where one girl could carry both roles, reflected how deeply embedded Mr. Ayiro was in both the formal and informal structures of student leadership. In some ways, the fusion of C.U. and entertainment wasn’t just cultural – it was, in part, curated.

Mo also happened to be a French student, performing solo verses in French during the Kenya Music Festivals. Although Mr. Ayiro taught German and Mo studied French, she recalls that their co-curricular paths often overlapped during festivals, sometimes coincidentally, since French and German students would usually share a bus.

“All through the year, in terms of co-curricular activities, he was the dominant patron in almost everything I was involved in… In a single week, I’d see him four or five times, where we’d have to speak face-to-face, at length, about different things.”

Their friendship, on a personal level, was deepening too. “When I had a hard time in my life – like something happening in school with my academics or in my social life, I’d still go to him for advice. There was trust being built on that side.”

Mo says that being close to Mr. Ayiro made her feel valued. Important. Seen.

“He’d reference me a lot in his sermons and C.U. teachings, like giving me shout-outs or using something that happened when we were together to illustrate some point. Sometimes, he would leave a card for me that would say something like:‘Thank you so much. You're a blessing. You're a gift.’”

It also gave her material benefits in school.

“Because of that proximity, I was in every drama outing, I’m going for every mission. When he went to preach outside school on weekends, I’d be on the list. Suddenly, I’m seeing Nairobi, Kiambu and so many counties in new ways; I’m entering spaces I wouldn’t have otherwise. And I knew he was giving me those opportunities because of our relationship.”

Mo even remembers being selected for an exchange program to Denmark.

“Honestly, I had no business being there. It was meant for German students. I didn’t even take German, and somehow, I was on the list.” She didn’t end up going, but she still notes it as an opportunity offered to her.

By the time she was in Form Two and Form Three, Mo was spending significant time at school even during the holidays – often around Mr. Ayiro. There would be a week or more at the Drama Festivals, followed by another stretch helping to organise Upgrade Program, a youth camp that brought together pre-teens from different primary schools for a weekend of fun, fellowship, and ministry.

The camp was hosted at Alliance by Ken Gomeri, a youth pastor and close friend of Mr. Ayiro, who also doubled as Bush’s volunteer hockey coach. These extended periods of activity outside of regular term time meant that Mo remained within Mr. Ayiro’s orbit long after other students had gone home.

Several times during the Drama Festivals, there is a lot of downtime before and after performances, or when you’re waiting for the winners in your category to be announced.

She remembers that Mr. Ayiro used to like people-watching, with the girls, just giving random commentary on people passing by. Sometimes, the conversation would drift into Mr. Ayiro ‘rating’ the women passing by as they were going about their day, asking the girls if they thought men liked what this or that woman was wearing.

“One time, after our performance – because we performed in the first two days – after that we were just hanging out. He would tell us what turned him on, and what he liked physically in a woman. I was in Form Two at the time. We would just sit there, listening, quiet, sometimes giggling.”

Mo remembers one Sunday after the school chapel service, while she was collecting the hymn books.

“He stopped me while I was leaving and said, “Hi babe.” That’s when he started calling me bae or babe. It was Form Two, term two. That was his pet name for me. He would only call me that when no one was around, and the thing is, we were constantly working together in all these different spaces. And he’d still do little things – wink at me when talking about tasks, like cleaning or organising something. He’d tell me I was pretty. That I was hot. That I was attractive.”

Mo says she didn’t know how to process it. “I didn’t have the language for it. I just told myself, ‘When he says babe, he doesn’t really actually mean babe.’ I tried to rationalise it.”

***

Mo completed high school in 2017 and remembers feeling an immense anxiety that she was about to lose a very important pillar of her life.

“Mr. Ayiro had been a constant presence throughout my entire high school journey, starting in second form. It had been an intense three years – where I’d see him every single day. He was there for everything – youth ministry events, drama trips, going to Music Festivals, visiting all these counties and regions.”

“I attributed my growth to him. I told myself, ‘Because of Mr. Ayiro, I became C.U. chairlady. I learned how to organise events. I learned sound, logistics, how to set things up. I got those leadership skills because of him.’ All these opportunities, in my mind, were because of him and no one else.”

She remembers a few months of trying to figure life out, and then she met up with him again in mid-2018, when she went back to the school for a weekend challenge. Former students – “old girls” – had been invited, and she decided to go.

“I remember – we hugged. I was so happy to see him, because I felt like I’d been living my life without this crutch that had carried me for three years.”

The former students were all in the staff room, catching up with their old mentor between C.U. sessions.

“He waited until all the other girls had left the staffroom, and then he gave me a peck on the cheek. He looked at me very intensely and said, ‘I’ve always really loved you.’ And I said something like, ‘Okay... yeah, I kind of know that.’ But I meant it in a mentor way, as in, ‘you’re important to me, you’ve shaped me.’”

Mr. Ayiro then said he said he was sad that she hadn’t kept in touch after she finished high school. That he thought she’d moved on. “He said, ‘Like the rest of the girls.’ That was the beginning of him treating me in a very different way. A way that was confusing.”

After that day, he’d text her here and there, chatting her up, asking how things were going. Once, they met up for coffee, at Java Koinange Street.

“At that Java meeting, he told me he was so sad that I was no longer in his life.

He said, ‘We should stay in touch.’”

Mo agreed, and she was so glad to have him back.

“And then he said, ‘I’ll never leave you.’ He said, ‘I’ll always be there for you. Whatever happens. I’ll always be there for you.’ He even said, ‘If you ever want me to help you with guy stuff, I’ll be there.’”

Mr. Ayiro went on to start inviting her for different events within, and outside, Bush – a weekend challenge here, a drama festival there.

***

Mo explains that it was not unusual for old girls to spend the night at Mr. Ayiro’s house. Saturday evening C.U. meetings end after 8.30pm, and many of the old girls would attend and afterwards, simply go to his house within the school compound, stay the night as a group, and leave together in the morning.

Mr. Ayiro lived in this house during the week but wouldn’t spend the night there with them on nights like this – he was married and he and his wife had a house in Lang’ata, though maintained his house in the school. Furthermore, it would be a madhouse of a dozen girls sleeping on the floor in the living room of the small, one-bedroomed bungalow, giggling and chatting through the night. He’d just walk them to the house, hang out a little bit, and then drive to his Lang’ata home.

This pattern had been normalised over time, becoming part of the unspoken culture within the C.U. and wider Busherian community. For girls who were still students or recently graduated, the practice raised no red flags – especially when they saw others doing it before them.

To understand how easily boundaries were blurred in Mo’s story, it’s important to understand the culture of Alliance Girls High School. As one of Kenya’s most elite public boarding schools, Bush doesn’t just impart academic excellence; it fosters a deep sense of loyalty, belonging, and obligation among its students. From the moment a girl arrives in Form 1, she is immersed in a tight-knit, high-achieving sisterhood with its own rituals, language, and lore. Leaving Bush doesn’t end that connection. In many ways, it only deepens it.

For generations, giving back to the school has been framed almost as a duty. Old girls return for mentorship, to support clubs like the C.U., drama, or music, or even just to show up at school events as a way of keeping the flame alive. The school encourages this involvement, and students are taught – implicitly and explicitly – that staying connected is both noble and necessary.

These alumni networks are not just sentimental. They have real material benefits. In a country where networks often determine access to jobs, scholarships, and opportunities, being an “old girl” of Bush is a passport into elite professional and social spaces. Senior government officials, diplomats, CEOs, and renowned academics often proudly cite their Alliance roots. For younger alumni, especially those just a few months or years out of school, staying close to Bush can feel like keeping a foothold in a powerful network.

This is part of why returning to the school for C.U. meetings or drama festivals felt so natural, even expected. It's what Mo and others had seen older girls do – and what they, in turn, modelled for those coming after them. It was framed as a form of service, of mentorship, of leadership. And in this atmosphere of trust and reverence, someone like Mr. Ayiro – respected, spiritual, and deeply embedded in the school’s culture – was often given the benefit of the doubt.

In other words, when girls stayed over at his on-campus house after evening C.U. meetings, they weren’t doing something necessarily secretive or forbidden. They were participating in a culture that had been normalised over time, a practice passed down from one cohort to the next. This context made it difficult for any one girl to question what was happening – especially when she had seen others do the same before her, and when she believed she, too, was giving back to a place that had given her so much.

One time, Mr Ayiro invited Mo for a drama event in the school. Her yearmate Faith* also came along, and the two girls spent the night at Mr. Ayiro’s house.

“That morning, Faith left early. I stayed behind. When I woke up later that morning, I met him at the admin block to say goodbye. And he told me, ‘I was so tempted to come to the bed and cuddle you up.’”

He hadn’t spent the night at the house, but she heard his footsteps in the living room at some point very early in the morning.

“He must have come from morning devotion. And what he said – as sweet as it may have sounded – it terrified me. I still remember that feeling.”

The slow escalation had begun.

***

A few weeks later, in June 2019, there was another event she was to go on – this time, for another weekend challenge at another school, where Mr. Ayiro had been called to preach. He asked if she’d like to come to Alliance first, spend Saturday night, and he’d pick her up from there on Sunday morning. She agreed – it just seemed easier, logistically.

During that Saturday, while she was attending C.U. with the students – and, of course, Mr. Ayiro – the power went out. Electricity blackouts weren’t unusual in Kikuyu, but this time around, because the blackout happened close to the end of the C.U. session, those who were leading the fellowship decided to end it early and let everyone head on back to the dorms.

Mr. Ayiro told Mo he’d walk her to his house, and so they left – walking behind the classrooms, beyond the spot where the school bus was usually parked, and past the basketball court, to House #30.

The power hadn’t come back when he unlocked the house and they got in. There was a table right at the door – a large, sturdy worktable where he’d put some of his books, his things. Mo was getting ready to hug him and say goodbye to him, when he leaned against the table, and said one word to her that would change everything.

“Come.”

She went to him and he held her close, very close to his body.

“He was rubbing my back. One hand went under my sweater. Under my T-shirt. My heart was racing.”

“At this point, I’m so afraid. I don’t even know what to think. What to do. I’m confused. I just saw him teaching in C.U. before the lights went out. He’s married, and we’re going on a mission tomorrow. And now – he’s pulling me by the waist.”

Mo didn’t stop what was happening. She went along with it, she says, because it was all so unfamiliar to her. He was caressing her body, kissing her neck, holding her the whole time.

“I’d never hugged a guy before. I didn’t know what that felt like. I didn’t know what it means when a man who is turned on hugs you. And I’m just thinking it felt so bad. It felt so wrong. And then he tries to kiss me. I’m moving my head away.”

She doesn’t remember how exactly it ended, but at one point he told her he had to go, his wife was waiting for him. He left, and she was now in his house, all alone, in a daze.

She remembers trying to understand what had just happened, and why. What it meant. Over and over. She barely slept that night, and at 5 a.m., the agreed time, he came and picked her up to go on the mission to that other school. In the car was Mr. Ayiro, his wife, and another colleague, the school’s drama coach.

“I got in the car, and I had to act like nothing happened. After the mission – after he preached – we were sitting together having food. And then... he would just wink at me. He stretched his leg under the table, reaching across to where I was sitting. And his wife was right next to me. She was asking me how school was going; I was at a local university at the time. She was inviting me to her house. And meanwhile, he’s there saying things about me like, ‘You know me, I love this girl so much. My whole heart – this girl has it.’”

Mo sat there, completely perplexed, at how to hold what happened last night, and what was happening now, together.

But that was only the beginning. After high school, Mo gradually became more and more enmeshed in Mr. Ayiro’s life. She joined him on mission trips, regularly attended mentorship events at Bush, and often slept over at his house on the school compound. Most times these sleepovers included other former students. What emerged was a tightly woven world where certain “old girls” were not just visiting their former teacher – they were becoming part of his life.

“It was like I was his niece, or younger sister. That’s how it appeared, from the outside – this mentorship relationship. But privately, he was treating me very differently.”

***

In October 2019, Mr Ayiro invited her for a movie.

She recalls, “I thought – Okay. Why not? Because in my mind, I had heard ex-C.U. girls saying that Mr. Ayiro usually takes them for movies.”

She picked the movie: Angel Has Fallen. She deliberately picked an action movie, she says, and not a romantic comedy or a drama or anything like that, because she didn’t want that kind of energy between them. She outlined what happened next in her journal entry from that day, which she shared with me. A small excerpt of the diary is below, and what follows here is reconstructed both from her journal and an interview with me.

An excerpt from Mo’s private journal, dated 9.10.2019. Mo has requested for this to be blurred because she doesn’t want her handwriting on the Internet, but we can quote the journal entry above. It reads: “Yesterday I met up with Mr Ayiro. It was at around noon at Panari, we were going to watch a movie, Angel Has Fallen. So si we got into the cinema and sat with our soda and hot dogs. Immediately we sat down he touched my thigh and held…:

“He started rubbing my thighs, then he took my hand and put it on his private part. He says, ‘Feel it. That’s how much I feel about you.’ And it’s in the middle of a helicopter being hijacked – in the middle of an afternoon action film.”

Mo remembers feeling frozen, feeling dissociated from her body, like she wasn’t really there, like she was watching someone else doing what she was doing.

“I’ve never felt the private parts of a man. I don’t know. It was all new and foreign. At first, I was disgusted. But I also couldn’t visibly express it. Because I knew him. I’d been around him.”

Mr. Ayiro always had an inner circle – a small group of students he mentored closely, who had his attention and access. Being in this circle felt special, like a reward for being spiritually mature or exceptionally gifted. But his approval was also volatile. He could suddenly turn cold, withdrawing affection or access without warning.

Mo had seen it happen before: fellow student leaders who once seemed like his favourites would suddenly fall out of favour. He would speak about them afterward with finality – calling them prideful, misguided, or even predicting they’d never amount to much.

This unpredictability bred anxiety and hyper-vigilance. The fear of being discarded could drive students to cling even tighter, trying to win back his attention or avoid falling from grace.

“I knew what it looked like when he turned on you. And I told myself – That’s not about to be my life story. So I gave in.”

After the movie ended, they walked back to Mr. Ayiro’s car. He opened the back door, and Mo realised he wanted her to go into the back seat. Mo opened the front passenger door instead, and sat in the front.

“He said, ‘Oh, I thought you wanted us to go to the back seat.’ And I said, ‘To do what?’ I even laughed a little – like, ‘To do what?’”

He then asked her if she was free that afternoon, if they could go for a drive. Mo had other things she was supposed to do in downtown Nairobi. But he persisted, and she went along with this drive, and he took her to his house, at the teachers’ quarters at Alliance Girls High School.

“[At this point], I knew what was about to happen. I started feeling dizzy. I remember that scene – crystal clear. It was the shock. The fear. The anxiety. He said, ‘Okay, come sit on the bed.’ So I sat on the bed, holding my head.”

Mo remembers feeling like she couldn’t breathe. She was seated, and he was standing over her. He asked her how she was feeling, and she told him she was feeling like her heart was racing.

“And he said, ‘I want to feel it.’” Her heart. “So he slips his hand down to where my left upper breast is – he places his hand over my heart. Then he slips further, and holds my breast.”

He asked her if that made her feel better, and she said she wasn’t sure. They lay down, and he was holding her as they lay on the bed. He told her he thought she was going to leave him.

“I remember he told me, ‘Everyone always leaves me. Because I’m so good at hurting people.’ He told me, ‘God has given me a talent. And the talent is to hurt people.’ And he said, ‘I’m afraid I’m hurting you right now.’ He said that.”

At this point, Mr. Ayiro started to apologise to Mo.

“He told me that he was scared I was going to look at him differently now, and that he was disappointed in himself that they were there. ‘That this is what we’ve become.’”

The confusion was not just about the apology – it was about who was offering it. Because if we zoom out, this wasn’t just any adult. This was Mr. Ayiro: the man who had led C.U. with impassioned sermons about integrity, purity, and moral uprightness. Week after week, Mo had sat under his teaching, internalising his exhortations to flee sexual immorality, to avoid “compromising situations” with boys, and to live above reproach. She admired him, looked up to him – she had believed him.

And now, here he was, not only crossing those very boundaries he had drawn so clearly for others, but also appealing to her for comfort. He spoke of his fear of being abandoned, of everyone eventually leaving him. His sadness seemed genuine. But that, too, created more confusion.

It was a moment of searing cognitive dissonance: the same man who had cast a vision for spiritual purity was now testing the limits of Mo’s physical and emotional boundaries.

The man who said “flee temptation” was now positioning himself as a wounded figure deserving of empathy, even in the moment of his wrongdoing. Mo remembers telling him gently that she wasn’t physically attracted to him, hoping to reset the boundaries. But that seemed to make him even sadder.

“I felt sad for him. I hugged him, and then a little while later he drove me home.”

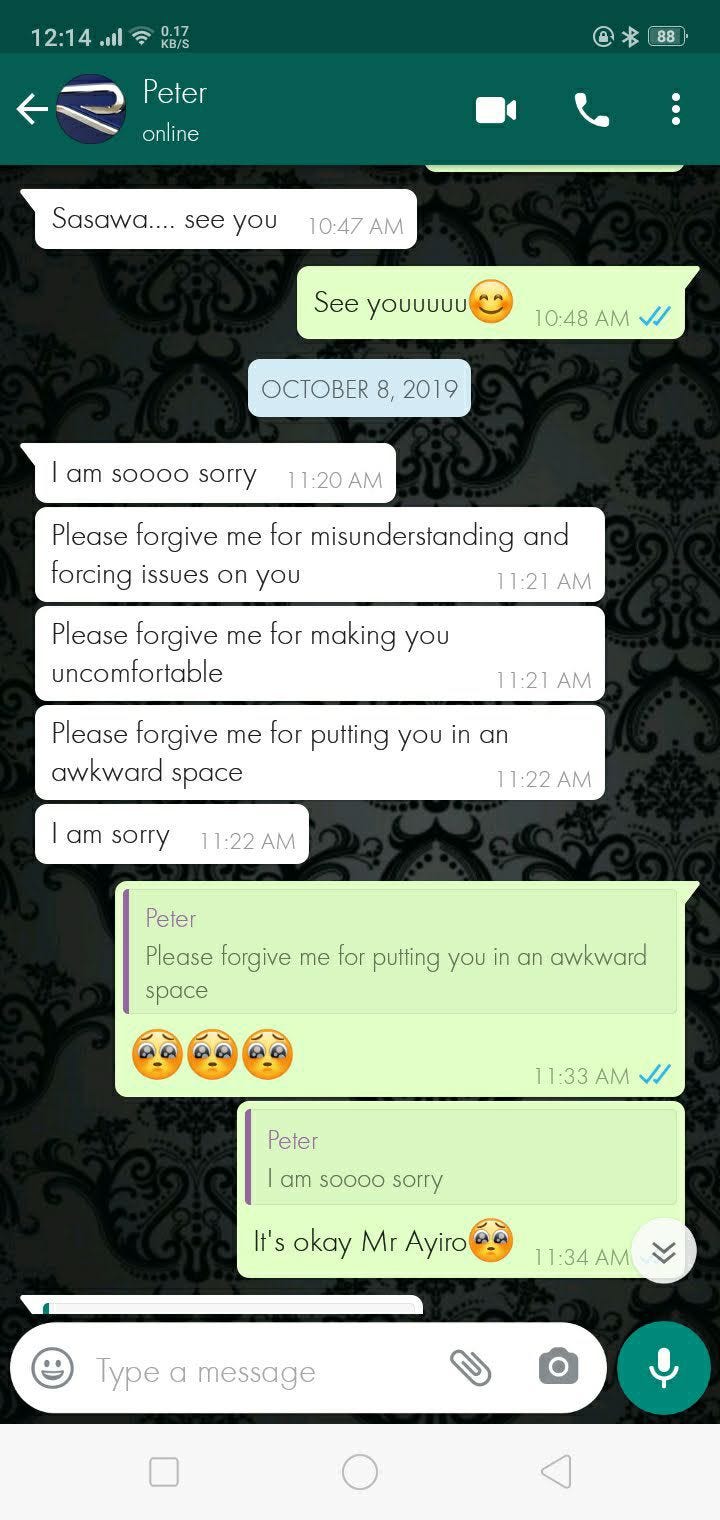

The next day, Mr. Ayiro sent her the following texts on WhatsApp, which Mo shared with me.

I am soooo sorry

Please forgive me for misunderstanding and forcing issues on you

Please forgive me for making you uncomfortable

Please forgive me for putting you in an awkward space

I am sorry

She replied, “It’s okay Mr. Ayiro.”

***

In the ensuing months, Mo says Mr. Ayiro worked hard to win back her trust. He took her on chaste coffee dates, and continued to have her tag along on missions to other schools and churches where he had been invited. She even continued to have sleepovers at his house, typically in a group of other old girls.

“He seemed deeply remorseful. Or at least I thought so. And that made me think: “Okay… maybe it’s possible for me to be close to Peter without this being sexual.”

She doesn’t remember when she started thinking of him as Peter, not just Mr. Ayiro, but it was somewhere around this time. She was 19, and he was 44.

One day in late 2019, he invited her for another teacher’s wedding. The wedding was going to be all the way in Bungoma, and as usual, the plan was to make it a group outing with other ex-Busherians. He suggested that Mo, and another ex-student sleep at his house in Bush, and then he’d pick them up very early in the morning to drive to Bungoma.

“I went to Kikuyu the night before the wedding. And the reason I go is – I’m feeling confident. I'm feeling comfortable. Because for the last like four months, nothing had happened between us. All of that was in the past, or so I thought.”

When she arrived, it turned out that the other girl who was spending the night hadn’t arrived yet – Mr. Ayiro was actually going to pick that girl up later.

This was the first day Mr. Ayiro had sex with Mo, in that interim period between Mo arriving at his house, and the other girl being picked up.

As it happened, Mo remembers being very tense, like her body was made of concrete or lead. Mr. Ayiro noticed it too. “He asked me why I was so tense, and that I should just relax. He kept on telling me to relax.” She didn’t know how to make her body relax.

Mo says that after this, he went and picked up the other girl. The two girls spent the night at Mr. Ayiro’s house, and in the morning, he drove to Bungoma with them as promised.

When they got back from the wedding the following day, he had sex with her again, in his house. She felt that she couldn’t say no, since it had already happened the previous day.

“And the thing is, I never wanted him. I think that’s what made it feel like such a violation. I never even wanted him. I felt robbed of something. Because it wasn’t just what happened – it’s that I didn’t invite it.”

Mo says that this was the escalation of what ended up being a rollercoaster ride of a relationship, if she could even call it that.

“That’s what characterised our relationship. He harms me. Then he says he’s sorry. Then he goes on this whole emotional spiral. Then I’m the one comforting him. And then he does it again. It was a cycle. That was the whole cycle.”

Mo remembers one incident that is seared in her memory. It was another one of those times when old girls had been invited for a drama event that was happening in the school.

“He asked me to walk him to his house to pick something up. Before this day, there had been another instance when the same thing had happened – I was in the school and we went to his house to pick something or the other, and nothing had happened.”

So this particular day, Mo says that her guard was a little down.

“What ended up happening is that he kind of ambushed me once the two of us got to the house – he was all over me, and there’s a part of me that felt defeated, like, oh my God, I’m already here, what can I do?”

On this day, the condom broke. Mo immediately panicked and started stressing – what if she got pregnant?

“He drove me to Kikuyu town, in his car, and then gave me money to buy a P2 [an emergency contraceptive]. There were so many heavy, negative emotions for me in that moment. We get back to school and we immediately go for a C.U .session where he was preaching. I just couldn’t stay for that. I couldn’t. I went home that day.”

A few days later, when the pregnancy scare was over, Mr. Ayiro reached out to her.

“He said that he wished that I wanted him the way he wanted me. Then he said he didn’t know what he would have done if I had conceived a baby out of rape with him. He said he didn’t know what would have happened to my future.”

Mo says he called the sexual experiences they had rape. She said that word came from him.

“He said it. He called it that.”

***

As the new year of 2020 came along, Mo remembers struggling with her health. She didn’t feel well most of the time. She was constantly anxious, struggling with pain in the pit of her stomach, bloating or constipated, and increasingly feeling like she was living a real-life nightmare.

Her relationship with Mr. Ayiro was still on and off for the better part of 2020. She recalls he’d begun to send her links to online sexual material, things he wanted them to try the next time they were together. She’d try to break things off with him, only to feel like it was futile, that she could never escape his orbit. He had been her first sexual experience after all, and wasn’t that supposed to bond you for life?

“It was like I was forcing myself to love a relationship I never even wanted to begin with. It kept going – on and off – until one day I asked myself, what is this? And I just started feeling so far away from God.”

Mo says she realised she had been waiting for Peter to be the bigger person, to be the Christian man she had once known, and to come to his senses and end this thing.

“And I remember just feeling it, deep in my spirit – I have to be the one to get myself out of this madness.”

Mo remembers a season of thinking about what to do next. “By this point, I was really taking stock of my life. I was always confused. He wasn’t supportive. He was mean. I couldn’t even define what this relationship was. I felt like he was messing with my mind. He was driving me crazy. And he was using me as a sexual object.”

Mo says she didn’t want to become like some of the ex-Busherians she had seen while she was still a student, those “whose lives become tethered to Peter.” Because she remembers some former students who would even bring their husbands to be vetted by Peter.

“And I was like, what madness is that?”

Around August, she started telling him, on text, that she wanted to meet him to talk about some serious things.

“For like a month – he refused to pick my calls, ignored my texts, wouldn’t give me a time or date to meet.”

She kept on texting him, asking if he’d give her an audience, and was not getting a response. Eventually she thought she’d start showing up to where she thought he might be. Mo calls this season her Diary of a Mad Black Woman era.

In November 2020, her old friend Faith*, whom she had spent many nights at his house, told her there was going to be a mentorship event for fourth formers at the school. She knew this was her opportunity.

“We went to school. He didn’t even look at me. Not once.”

Mo and Faith slept at his house that evening, like they had done many times before. But this time, Mo decided she wasn’t going to leave until she had had an audience with Mr. Ayiro.

“I told myself, I’m not leaving this house until I say everything. Everything. Because I knew he had to come to the house at some point that evening. And if he didn’t, I was going to lock myself in.” Again, we must remember this was her Diary of a Mad Black Woman era, she says. She calls it her real-life Tyler Perry movie.

Faith left later that day, and eventually Mr. Ayiro arrived at the house late – around 7pm.

“And I told him, Peter, sit there. I didn’t even call him ‘Teacher’ or ‘Mr. Ayiro’.

For two hours – I poured out everything. The hurt. The betrayal. The confusion.

How he had broken me. How he had used me.

How I never even liked having sex with him.

How confusing it was being around his wife.

He tried to start saying something, and I told him, ‘Don’t even try to leave. I’m not done.’ I asked him, ‘Have you ever thought about how I must have felt?’

I said everything. I was crying. I was yelling.”

Mo remembers telling him: “I know I’m not the only one. I know it. You’re mad. You need help.’ And then I went back to: ‘I am so, so disappointed in you.’ I felt like that was the beginning of the burden being lifted. That’s what allowed me to begin healing.”

Mo says Mr. Ayiro listened quietly, and then left, to his house in Lang’ata, the house he shared with his wife.

“I remember thinking, What is this life I’ve been living? But I was so proud of that moment. That day – I will never forget. That was my liberation day.”

***

After breaking off the relationship, Mo descended into a mental and emotional spiral. She wasn’t done with him – not yet. In the aftermath, she sent Mr. Ayiro a series of long, emotionally charged text messages. In them, she tried to make sense of what had happened, reiterating what she had already told him face-to-face, as though writing it down would make it more real. Almost none of the texts were ever acknowledged or replied to.

Reading through these messages is like witnessing someone unravelling in real time. The texts trace an erratic journey through the five stages of grief – denial, anger, bargaining, sorrow, and, at moments, acceptance.

But the progression is far from linear. Mo loops from acceptance back to rage, slips into bargaining, and then sinks again into sorrow. These sprawling, often repetitive texts read like a desperate effort to construct a new version of reality – one in which what happened really did happen, and now she has to live with that truth.

In one of the few messages that Mr. Ayiro responds to, Mo writes:

Mo: Whenever I said I felt taken advantage of, you’d turn things around and try tell me that it was love you were showing me, you’re pathetic! And yes I’d still say that to your face because you did rape me and played psychological mind games with me and that’s unfair. Mr Ayiro what you did was unfair. I hope you get to talk about everything and say something, because your silence is the worst. I hope no other young busherian gets to go through this

Mr. Ayiro: Deep stuff

She also wrote handwritten letters that she never sent. In these letters, she dug deeper into her confusion and pain. She revisited her early memories of him as a student. She wondered how he could be the C.U. patron while leading an apparent double life. She questioned why he had been so inconsistent – so attentive and intoxicatingly affirming one moment, and so dismissive, even cruel, the next. She was trying to grasp how someone who had made her feel singular and chosen could also be the source of such destabilising harm.

Eventually, she asked to see him again, feeling like she still needed to say some more things. She wasn’t holding out for an apology; she was wondering if there was something she could say that could get a reaction, just an acknowledgement from him.

After weeks of stonewalling, he responded by text. The text reads: Meeting would be inappropriate.

She continued pleading, asking if she could see him, saying she wanted to make things right and get done with all the anger and pain. He responded: Interaction with people who do horrible things to others and hide behind their positions is both ill advised and inappropriate.

It was around this time that she shared what she was going through with Diana*, an older, former student of Alliance, who knew Peter Ayiro both from school and later from being a member of his home congregation.

She also shared it with Priscah Njuguna (neé Matende), an old girl from the class of 2001, who was her small group leader at church. Both Mo and Priscah Life Reformation Centre in Githurai at this time, a congregation that was part of the Congress WBN network.

“Priscah was my Bible study/ small group leader. Early on – like, let’s say when this was happening – I had confided in Priscah, but it was in the context of, ‘I’m doing something I shouldn’t be doing with this random boy.’ Priscah [supported me] because I felt like I wanted my actions to match my beliefs. So after confronting him, I told Prisca, ‘You remember that story I was telling you? It was Peter.’”

Priscah and Diana attempted to get accountability through the Congress WBN church structures, as outlined in the first part of this investigation The Teacher and The System Part I. They have both corroborated Mo’s account here.

Ultimately, Priscah and Diana failed to get traction, as institutions seemingly closed ranks to protect Peter Ayiro.

***

Mo was preparing to move to a new town in 2021.

The transition marked a turning point – not because of the distance itself, but because it aligned with an inner shift already underway. Mo says that the break was psychological before it was physical. She had begun disentangling herself emotionally from Peter’s influence, a process that took deliberate effort.

The upcoming move created a natural deadline. But the real work of separation wasn’t about where she was going; it was about what she was finally ready to walk away from.

This decision also cost her a network that, for many Bush alumni, lasts a lifetime. At a school like Alliance, the alumni circle is not just a community; it’s a tribe, a pipeline to opportunity, belonging, and lifelong friendship. To lose that is no small thing.

“I had to distance myself from the Busherian circle and figure out who I wanted to stay in touch with. That’s also why I insisted on meeting him because I wanted closure. He was being cagey and dodging me, but I wanted him to know the full extent of what I felt. He never responded.”

But in the aftermath of the break, she simply couldn’t hold both her healing and those ties. Not when some of those same friends were still allied – directly or indirectly – with him.

“By then, I’d reached a point where I was like – If you’re Peter’s friend, or your friend is Peter’s friend – you are out of my life. I removed everybody who even tolerated him. I didn’t want anyone around me saying, ‘Let’s pray for him.’ I didn’t want that.”

This zero-tolerance boundary came at a steep cost.

“I lost so many Busherian friends. And you know – when you’re from Bush, that’s like your circle of lifelong friends. But I had to lose that. Because I just felt – I’m not going to keep people in my life who are minimising what happened.”

Once she broke things off with finality, she expected relief, but instead found herself in emotional freefall. The break from his influence didn’t immediately translate into peace.

“The first four months were incredibly hard. It honestly felt like withdrawal. Like I was in rehab. My mind had been conditioned for so long – not texting him, not reaching out, not seeking his advice or approval – it was excruciating. It was like trying to get off a drug.”

What might appear, on the surface, as a relationship between two adults (albeit extramarital for one of the parties), was in fact a system of control – engineered through emotional dependency, spiritual manipulation, and institutional protection. Mo had to deprogram herself from what was essentially a one-man belief system, where he was the teacher, the mentor, the father figure, the gatekeeper to community, and the spiritual authority.

“All those years, he’d been a co-author of my life,” she said. “When I ended things, I was 21. And I had to ask myself: who am I now, how do I write my life without him? That’s the identity crisis I faced.”

What Mo had experienced over the years was a total collapse of trust across every layer of her life. It was abuse dressed up as mentorship, psychological manipulation masked as concern, and a profound breakdown of integrity – institutional, relational, and spiritual. The very systems that should have safeguarded her instead deepened the harm, leaving her to reconstruct not only what had happened, but who she was outside of his shadow.

Still, with time, and through therapy, new friendships, and a church community that respected boundaries, Mo began to heal. Slowly, she reclaimed her sense of self.

“In time, I rebuilt my identity – my entire teenage life had been so shaped by him. But I learned I could actually stand on my own two feet. That realisation was a huge liberation. I’m so grateful that I chose to believe there was more ahead for me without him than with him.”

Mo is 25 now. She says she has done, and is still doing, the work – unpacking the psychological abuse, the mental abuse, the sexual and spiritual abuse.

“And now I’m in a local church where things are just… normal. Things are handled well. People are regulated. God is still honoured, but in a way that doesn’t ignore how people are treated. This part of my life has become a healing journey.”

“Now, I can be part of a church without that constant fear – that someone here will abuse me. That fear is no longer in the driver’s seat. I’ve worked through so much, and I'm still working through it.”

***

Have you experienced something similar to what has been outlined here, or do you have insight to share? This story is part of an ongoing effort to understand the wider systems and silences that made this possible. If you’re a former student, teacher, parent, or anyone with information or reflections to add, you’re invited to reach out. You can write to us confidentially at 109walkinthelight@pm.me. All correspondence will be handled with care, and no information will be published without your explicit consent. Your voice could help bring greater understanding – and accountability.

Has something in this story brought up some emotions that you need help with? Here is a list of counsellors and therapists in Kenya that you can reach out to.

The rot that has been covered up in the Alliance Girls High School is just the catalyst. This is a systemic issue in many girl schools. But the time has come to expose the men and women who've caused our girls all this pain.

Waaah this is indeed psychological abuse masked as mentorship, hugs to Mo and even Ken Gomeri should be exposed, the two of them also had their talons in other schools especially within Nairobi. I was in Kenya High school and there was a lot going on in weekend challenges to a point during my time our principal Mrs Saina barred other schools and mentors from attending these weekend challenges.