By Christine Mungai

“We struggle not because it assures us of victory. We struggle because it assures us of an honorable and sane life.” ~ Ta-Nehisi Coates

Prologue: #IWentToAlliance

I joined Form One at Alliance Girls High School in February 2000. Established in 1948 as the first school for African girls in Kenya, Alliance - or ‘Bush’ as it was nicknamed – carries a storied legacy of excellence, discipline, and leadership. It shaped generations of formidable women and is widely regarded as the country’s most prestigious girls' secondary school.

I was 13. My parents were in the process of divorcing and it had been difficult to understand what was going on. I mean, I had never heard them fight or argue. That’s what makes parents divorce, right? I was eager to leave home, its hurt and confusion behind, and start a new chapter in my life in boarding school.

On the second day of school, February 4th, 2000, there were just over 40 students in my class, most of us having obtained some of the highest marks in the end-of-primary school exams. Regardless of our achievements, at Bush we somehow knew that we were part of a constellation – we would no longer be the lone bright star of the dusty village school.

Only time would tell whether we had just been big fish in small ponds, and whether we really deserved all the accolades, the awards, and the adulation for being so clever. I wasn’t from a dusty village school and, in any case, we were all there in our freshly starched uniforms that still had the smell of School Outfitters. A new chapter had opened in our young lives and we were ready for the door to fling open.

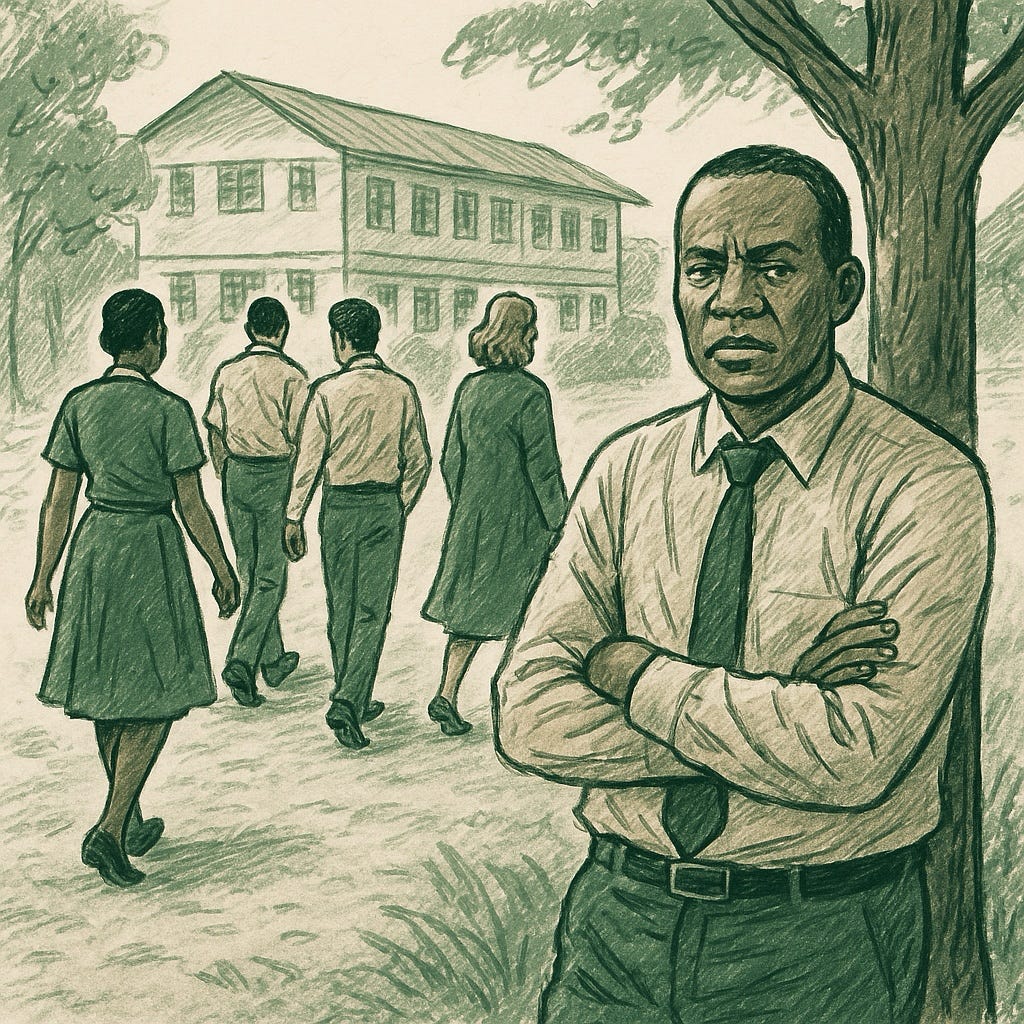

And then he walked in. My history teacher, Mr. Peter Ayiro.

I remember him as confident, funny, teasing, making little jokes about everyone. I remember being struck by his accent. He stressed his consonants and opened his vowels a little too much; it was an urbane, Nairobi, middle-class accent. At just 25, he was one of the youngest teachers in the school – most of the rest were as old as our parents. I didn’t know that people like him became teachers. I thought he could have done anything with his life. But he was a teacher.

Most remarkable of all, I think, it is that he had a sense of purpose. There was something laser-like in the way he taught us about the Arab Slave Trade and Berlin Conference of 1884. It burned most brightly in the mornings and on the weekends when he would teach the Bible and preach at the Christian Union meetings. I didn’t know anyone like him. We would talk and chat for hours – before or after C.U., in between lessons, here and there at the school.

By the time I left high school in 2003, I was 17, and Mr. Ayiro was more like a friend than just a teacher. In November that year I joined his church, where his father pastored at.

His friends became my friends and, now that I wasn’t that 13-year-old any more, my being his former student faded into a little quirky biographical note that was only mentioned in passing. During this time I saw him every week. I was involved in youth leadership at the church; regularly serving, planning events, and participating in group activities. I was older, but he was still on that pedestal. He was the most upright man I knew.

Then, in July 2006, he invited me to his house on the Alliance school campus. There was a mentorship event for the students to be held on a Monday morning, so he suggested maybe it would be easier for me to spend the night at his house on Sunday, then I’d start the day in school instead of juggling three matatus from home. That made sense, so I agreed. I got there on an ordinary Sunday afternoon. He was 31. I was 19, turning 20 in a couple of months. (I was a little apprehensive about leaving the ‘teen’ suffix behind forever. It seemed daunting, so I’d joke with my friends that I was actually turning ‘twen-teen’).

What happened that day was a physical, sexual encounter. There was no penetration, but a lot can happen without that. The encounter wasn’t forced, in the way we usually understand force. But it also wasn’t something I had the tools to fully process or navigate. In that moment, I didn’t say no – but I also didn’t fully understand what I was saying yes to. I felt disoriented, like I had stepped outside myself, like this couldn’t really be happening.

He was someone I had known for years. I trusted him. He still was a spiritual authority in my life. That context made it nearly impossible to see clearly, let alone resist. I remember feeling like I was swept up in a storm of conflicting emotions: excitement, terror, thrill, disbelief.

What shocked me more than the encounter itself was what followed. It felt like he pulled away completely – he became emotionally cold, and incredibly distant. I would see him every Sunday, but it was as if I didn’t exist. What I felt as that silence, that erasure, was somehow more disorienting than the act itself.

I didn’t expect to be discarded like that – that’s what it felt like at the time. And I didn’t have the language then to understand what had happened. I confided in two friends – both of whom knew him personally – about what had happened. They were surprised, and genuinely wanted to help, but it felt as though the focus was on helping me move on, not on addressing what he had done. One of them encouraged me to pray about it. I don’t remember feeling very angry. Instead, I felt hollow, lost, and very alone.

I went away to university, and when I returned to Nairobi a few months later, he instantly became friendly again, like nothing had happened. So I compartmentalised. I buried the experience so deeply that I convinced myself it hadn’t affected me. But like a tree stump with deep roots, it was always there, unseen. When the dissonance became overwhelming, I left that church.

And for twelve years, I carried on, believing that I was the only one. Thinking this way somehow made that moment such an aberration that I almost believed there was something about me that brought that out in him. That that wasn’t truly him. We even carried on being friendly, though we were never as close as before.

Then, in 2018, someone else told me it had happened to them, too. That changed everything. The moment I heard their story, mine became real. The distance I had constructed fell apart. Everything shifted.

All it took was one more voice. Until that moment, for 12 years, I had truly believed I was the only one. And that belief had made it possible to forget, to survive by not naming it.

What I’ve outlined above is my recollection of events. Peter Ayiro has never been charged in a court of law in relation to this or any similar incident. He has, to the best of my knowledge, never been held accountable in any professional sense either.

For a long time, I had no intention of writing this story. It was only when I began to hear multiple accounts that bore uncanny similarities to mine – accounts that spanned different years, generations, and settings – that I began to see a potential pattern; a forest, not just trees. Even then, I hesitated.

What pushed me over the line were two failed moments of accountability, in 2018–2019, and in 2021. In both instances, credible concerns were raised through both informal and institutional channels, and still, nothing changed.

This is not only a story about one man.

This is a story about the system that seemingly enabled him and appeared to protect him. It’s about how institutions knowingly or unknowingly close ranks. It is about how justice flounders in silences.

This is the story I’m here to tell, drawn from more than two dozen interviews with former students, teachers and staff of Alliance Girls High School, in their recollection, and largely in their words. Some sources have requested pseudonyms, marked with an asterisk (*) at their first mention.

At the time of publishing, the school’s board of management was made aware of the content, claims and concerns raised in this story. The board expressed shock and outrage, and promised “strong, decisive and immediate” action.

I.

Ask anyone who studied at Alliance Girls High School at some point in the past 25 years, and they can tell you about Mr. Ayiro.

He was Sheilah Mwiti’s class teacher when she joined the school in 2010. She had studied hard to pass her primary school exams, and felt lucky to be there. But the culture shock, the stress of being away from home, and what she immediately felt as immense pressure to live up to the legacy of Alliance, weighed heavily on her in those first weeks.

“He came across as warm and kind – like someone who really cared about the outcome of your life,” she recalls.

In Form One, he gave the class copies of the book ’The Purpose Driven Life’ by Pastor Rick Warren and told them to write an essay about what they thought their life’s purpose was going to be. They were 13-14 years old.

“It was a bit of an abstract exercise for Form One students, but he really seemed to want us to think about long-term vision,” she remembers. “He always emphasised kindness, and acknowledged that boarding school, and Alliance in particular, could be terrifying. But he reminded us to be nice, to be kind, and to look out for each other. That was very much his vibe.”

Peter Ayiro began teaching History and German at Alliance Girls in 1999, arriving at the school with a degree in Education from Kenyatta University. From early on in his career, he wasn’t exactly a rule-follower in the classroom. Ex-students describe him as a bit of a maverick when it came to his style of teaching.

Unlike many of his colleagues who stuck closely to the textbook and rote note-taking, ex-students say he often incorporated outside materials, like videos and supplementary readings, and encouraged students to think critically about the content.

His teaching style was at times unusually dynamic and engaging, more reminiscent of Western education systems that the students caught on television or in movies, than the traditional Kenyan emphasis on memorisation and exam preparation.

Some students thrived in that environment, but some struggled.

“Not everyone appreciated his Socratic methods of teaching through open-ended questions and conversations,” recalls one student, who asked to remain anonymous. “Especially if in primary school you thrived off of remembering facts, the Socratic way just feels strange. But I think it was something that I quite enjoyed, and so I very much looked forward to his classes.”

Sheilah remembers him having a bit of a “rogue teacher” reputation.

“Sometimes he’d just use the whole lesson to hang out with the class, just talking with them and giving them stories. And a lot of students really liked that, obviously, because it meant you got to chill instead of learning.”

Then, out of nowhere, he’d show up and give you a really tough exam, just to remind you that he was still a teacher. “I’d say he was kind of an oddball.”

Evelyne*, class of 2006, was one of those who didn’t like his teaching style. Outside the classroom, however, she considered him more like a friend.

“His office was one place I could walk in-and-out of freely. As a teenage girl in boarding school, it was just nice to get good attention. I didn’t think much of it at the time.”

Their conversations, she says, could be about anything – stories from home, how her day was going, how she was feeling. “There was always friendly chit-chat. I wouldn’t describe all teachers that way, though. To me, he wasn’t just a teacher – he was my friend. I respected him as a teacher, but I also knew he was my friend.”

The other thing old girls of the school will tell you about Mr. Ayiro, is that he was a born-again Christian, the co-patron and later, lead patron, of the Christian Union (C.U.) from the 2000s onwards. They talk about his undeniable role in their spiritual formation, in a school that has a strong Christian heritage and tradition.

Evelyne remembers starting her day with Morning Devotion, a morning prayer time that Mr. Ayiro started at the school in 2003.

“Morning devotion was a great way for me to start the day – personally, it just set the right tone. Since it was every day, it just became part of my routine. He’s the one who began it, which means I was seeing him every day.”

By the mid 2010s, Peter Ayiro’s status, influence and position in the school had expanded as he became a more senior teacher, and on the back of his born-again identity and patronage of the C.U.

In addition, his father, Pastor Aggrey Ayiro, had been one of the pastoral leaders of Chrisco Church in Nairobi in the 1980s and 90s. Peter was the first-born in the family of four sons, although there were numerous cousins and extended family members who grew up together and who, even in adulthood, would be considered part of the Ayiro home.

Pastor Aggrey would leave Chrisco in 2003 to start a new congregation, Kingdom Life Centre, but for a generation of evangelicals in Nairobi, Pastor Aggrey was widely known. Chrisco, too, was well-known as a nationwide network of evangelical congregations.

When Sheilah was a student in the early 2010s, Mrs. Dorothy Kamwilu was the school principal. She, too, reportedly professed her faith as a born-again Christian, as did her deputy principals. However, Sheilah recalls Mr. Ayiro as almost being a de facto deputy principal himself, due to the trust that the school administration, and particularly the principal Mrs. Kamwilu, had in him. Several former students and teachers have corroborated having this perception.

If you think of a school not just as a place where lessons are taught, but as a power structure of sorts, with ordinary students at the bottom, prefects slightly higher, then teachers above them and the school administrators over them all, Sheilah describes Mr. Ayiro in her time (2010-2013) as “right next to the principal” in the power structure.

“When I was there, Mrs. Kamwilu really liked him – like, really liked him… he and the principal were besties. He could do whatever he wanted. He could pull you out of class and take you to Chicken Inn – just for the vibes, I guess.”

Mrs. Kamwilu declined to comment on this story, saying she was now retired.

It’s not unusual for a teacher – especially one with such rapport with them – to reward students with small gifts to recognise their effort or good performance in a test, and the like. But several students from the early and mid-2010s say Mr. Ayiro went over and above, for instance by taking small groups of girls out of school to go to eat at city restaurants, like Java House, in the evenings, in his car.

That would be unusual for a teacher to do, especially because from the reports gathered as part of this investigation, there is no evidence to suggest that these were official trips sanctioned by the school.

It wasn’t always the same girls, but there did seem to be a favoured group at any one time. Other former students recall the teacher organising birthday parties for his favourite students – complete with cake – which by 2012 was against the school rules.

Several students from different years – even as recently as 2023 – said that being close to Mr. Ayiro came with benefits. Apart from the small gifts earlier mentioned, there was access to junk food to blunt the monotony of a boarding school diet. There were bigger perks too, like getting to be on a list of an official student excursion out of school, to outside church services, concerts, music festivals, and the like.

One student (class of 2020) described how Mr. Ayiro even seemed to have the power to influence who would go out of the country for international student exchanges or post-school scholarships – at least that’s the impression he gave them.

“It was almost like if you were going to hang out with Mr. Ayiro, you didn’t even have to do prep,” Sheilah (class of 2013) explains, of the weekday evening time for students to do assignments and independent study in class.

“You could leave dinner from the dining hall [at 6:30pm] and go straight to [his office] the German department, and leave there at 10pm – basically when you're going to bed. You didn’t have to go to prep, you didn’t have to attend a class. If you were in the German department hanging out with Ayiro, you could ‘unofficially’ miss classes,” says Sheilah.

The German department, along with most of the other teacher’s offices, was right opposite the main classroom block. If the lights were on at night, you could see right into the office – which means this was happening in the full view of anyone passing by.

How was this possible in a school with daily roll-calls, intricate rules about where students had to be at any given minute of the day, and prefects to monitor it all?

“Honestly, I think it was just audacity,” reflects Sheilah. “It was that kind of energy. And after a while, people started to believe it. Because if the principal is your homie like that... I really think that relationship is what catapulted him.”

Being friends with the principal seemed to give him a lot of credibility, she says.

It wasn’t just during Mrs. Kamwilu’s time. In the years that Mr. Ayiro has been teaching at Alliance, there have been seven school principals. Several teachers have described him as being “very close” to many of the previous school principals, especially from the mid 2000’s onwards.

Sheilah adds, “There’s also the fact that there never seemed to be any consequence, for what he did just solidified the idea that whatever he was doing wasn’t that serious. Like, it just became ‘his thing’, something quirky or funny that he did – haha – and not something to question.”

Achieng*, another student who joined in 2014, attributes this freedom and immense trust – and what appears to be clear boundary-breaking – to Mr. Ayiro’s reputation as a man of God, a person of integrity, and a faithful and dedicated Christian.

“Mr. Ayiro, along with the principal and the deputies during my time [2014-2017] were perceived as carrying a certain level of ‘anointing’, which was significant in shaping the way the school's administration functioned,” she says.

Alliance Girls’ High School’s motto, “Walk in the Light,” is meant to be a guiding principle – calling students and staff alike to live with honesty, courage, and moral clarity. But for some former students, that light may have cast long shadows too. The reverence afforded to figures like Mr. Ayiro seemed to create an environment where authority and anointing were conflated – and where questioning such figures was akin to questioning God himself.

As Achieng recalls, Mr. Ayiro’s apparent closeness to the administration gave him permission to bend the rules, all while cloaking his behavior in spiritual legitimacy. In such a context, “Walk in the Light” appeared to not be a standard to uphold, but a slogan that deflected scrutiny.

“He enjoyed full support from Mrs. Kamwilu, which is the reason why he told us he could take girls out of school. He openly attributed this trust to Mrs. Kamwilu, even when concerns were raised about his behaviour. It was a very tricky situation because everyone in the school knows Peter is a dangerous man to have around girls,” says Achieng.

II.

Achieng was an active member of the Christian Union at Alliance Girls.

“I think that teachers, especially male teachers, should never cross certain boundaries with students. But Mr. Ayiro did. I would say he would make inappropriate comments and give hugs that crossed the line – hugs where you could clearly tell something wasn’t right. You could see it, you could sense it, and it was impossible to ignore,” she says.

Achieng recalls witnessing him hugging girls tightly, “with his pinky finger and ring finger touching their bum,” but she would look away.

“I didn’t want him to see that I’d noticed. I did that so many times… I couldn’t let myself act shocked or uncomfortable. Instead, I’d look away and pretend it was normal, even though it made me uneasy.”

Achieng also got to witness how these things were handled in the C.U.

“I remember [him making] inappropriate comments to girls, saying things like, ‘You're so hot,’ or ‘I love you’, – comments that were entirely out of line. But if you ever asked him about it, instead of outright denying it or apologising, he would…deflect responsibility, by sometimes even volunteering more information, unprovoked…about how so many women [out there] want him.”

Peter Ayiro has denied ever hugging students in an intimate or suggestive way.

However, more than a dozen former students and teachers have corroborated that by the mid 2010s, there were widespread rumours about Mr. Ayiro and his conduct towards the students. And every year there seemed to be an inner circle – and muted discomfort.

“It wasn’t overt, like, ‘Oh, I think he abused this girl,’ but there were always whispers. It was like, ’I don’t think he’s doing good things in the German department’, that kind of thing,” Sheilah says.

“There was definitely competition for his attention,” she adds, describing how her deskmate once constantly tried to befriend him and get his validation.

“My deskmate would sometimes ask me, ‘Can you take me to the German department? I want to ask him something. I wrote him a letter. I want to give it to him. I want to give him this gift.’ It was that kind of thing.”

But this wasn’t merely adolescent frivolity or just crushing on a teacher. These were girls coming of age in a high-pressure academic environment, where excellence was the norm and adult validation was a scarce but prized currency. To be noticed by a teacher – especially one seen as cool, kind, and spiritually grounded – felt like a signal that you were not just smart, but seen.

What they were seeking, ultimately, was recognition. And in him, they found an adult who made them feel as though their voices, ideas, and presence mattered. It was that deep adolescent desire to be taken seriously.

He had a really “shiny” persona, as Sheilah describes it. “He came across as – ‘I can pull you out of class. I can take you to Java. I’m super religious. I’m chill and funny. I’m kind and fair.’ That made you crave his attention – it felt prestigious.”

Was he aware of the effect he was having on the girls?

“Of course he did. Do you know what a 14-year-old looks like when they’re really interested in something? They’re bright-eyed, eager, and hopeful,” says Sheilah. “Even without context, you can tell when someone is desperate for your attention. That’s not hard to see – especially for someone who’s intelligent.”

He couldn’t have missed it, Sheilah says.

“And on top of that, people were talking. There were whispers: You’re hanging out with these young girls a lot. It’s suspicious.”

“So, he knew. He knew there was some disapproval. But I think he got bolder. It was like – ‘yeah, people are saying things – but so what?’”

Four former teachers at the school interviewed as part of this investigation all say that the rumours were well-known, but there was never any first-hand, “concrete” evidence of anything untoward. No student ever came forward.

“This is something that has always disturbed me,” says one former teacher, who retired in the early 2020s. She asked not to be named. “There have been rumours all through, but he was so close to almost every principal in the school over the years.”

We contacted three former principals, whose tenures ran from 2004-2022. Two – Mrs. Janet Mbugua and Mrs. Dorothy Kamwilu – declined to comment on the claims made in this article. Mrs. Virginia Gitonga had not yet responded to our interview request by the time we were publishing this story. [To see how we researched, investigated and reported this story, see our accompanying note].

The teacher recalls a time when she confronted him about what she described as how he was “confusing and antagonising the girls”.

“I didn’t like how the girls were always seeking his attention, and how those who didn’t get it were taking it so negatively. I told him he should stop what he’s doing, it’s affecting many lives – these are kids. You know what he did? He put on his earphones as I was talking.”

Another teacher we spoke to explained that, in order for action to be taken, a formal complaint would have to be made to either the principal, or the deputy principal in charge of student welfare.

“He was untouchable. What could you say about him? I never had concrete evidence, but even if I did, I’d hesitate to present it to the principal. To put it candidly – I was afraid that I’d suffer the backlash and maybe even lose my job,” she says.

The teachers I’ve spoken to say that they ended up warning their students, privately, to be on their guard. One former student, Kim* (class of 2020), says that teachers would only go as far as saying that they should “be careful” around him.

“The teachers never used to pinpoint on anything, but several teachers were against girls doing German as a subject or joining the drama club where he was the patron. But at the time I never really understood the reason why they wanted to keep us away from him,” Kim recalls.

“The impression he gave us is that other teachers didn’t like him because he was a Christian, a believer, and had a staunch position on many things,” she says.

Achieng corroborates this position, saying: “He often used to tell us in the C.U. that ‘People are coming after me,’ or ‘People like me always face this kind of opposition.’ He’d claim that others were too afraid to confront him directly.”

Achieng tells me that in this moment, as a 15-year-old, she thought: “‘If he’s willing to be this open and vulnerable [with us], then those accusations must be lies.’”

She also remembers that Mr. Ayiro would often invite a particular kind of old girl to speak during C.U. meetings.

“The old girls he would invite to C.U. meetings [would] reinforce this idea of how he had been instrumental in their formative Christian years, emphasising the unique role he played, one they claimed no one else could fill,” she recalls.

This old-girl support system worked to reinforce the narrative that Peter was a safe and trustworthy person, Achieng says, making her disbelieve what she was seeing with her own eyes.

“Seeing these former students – girls who had gone through the same school – come back and say, ‘Oh no, he's a great guy; he really helped me when I was going through family issues or personal struggles,’ was powerful. It created a kind of cognitive dissonance because you were hearing these glowing endorsements.”

Another former student, from the class of 2014, recalls that he made it seem that staying in touch with him after school was, in itself, very important, or else your life might go off track.

“He convinced us that he could see into our souls. That he knew who was spiritually strong and who was slipping into the world. He’d talk about how some girls, after leaving school, had ‘abandoned the faith’ and stopped talking to him. He made it seem like not staying in touch with him meant you were backsliding.”

Sheilah wasn’t as active in the C.U., but she remembers an incident that happened in class.

“One time, Mr. Ayiro actually brought up an accusation himself,” she recalls. “He told us that someone out there had accused him of sexual assault. He said it in class during one of our class meetings.”

“The way he framed it, though, was like the real victory was that other people didn’t believe the accusation. So he gave us this speech – he said something like, ’I pray that all of you will have the kind of integrity that when someone accuses you of something terrible, your community will stand up for you because they believe in your character that much.’”

Several teachers remember an incident where a preacher, or perhaps it was a teacher, who’d asked everyone in the chapel who was a virgin to stand up. Obviously, practically all the girls stood up. It was that True Love Waits context back in the early to mid 2000s, the Nimechill era where sexual abstinence was a big message in church and youth spaces.

But they remember Mr. Ayiro standing up as well in this moment – and mentioning it in different contexts later, that he was a virgin. He was in his late 20’s to early 30’s at this time.

“He wasn’t married. He told us that he wasn’t dating either at the time,” recalls Sheilah. “He came across as completely non-sexual, a safe person. He really presented himself as a man waiting for marriage, as a man of God. That was his whole vibe: I’m not touched by worldly things. I love Christ. I’m pure.’”

III.

Evelyne remembers that something suddenly changed in her relationship to Mr. Ayiro when she was in third form. Until then, he’d been her friend, a confidante, someone she had prayed with at C.U. and at Morning Devotion. He was someone she’d been vulnerable with, and felt safe around. He had made boarding school bearable up to that point; he was frequently the highlight of her day.

“He completely cut off communication…I’d walk into a space where he was, and the usual way he used to acknowledge me as a friend was just… gone. He’d even avoid eye contact. And you know when something stops. Especially when it has been so consistent from the beginning, and then suddenly, it’s like you don’t exist.”

Evelyne says this left her in an emotional tailspin.

“I was really struggling – I even started kind of resenting the people he was talking to. Not because I minded him talking to them, but because I kept asking myself, ’What did I do wrong?’ It wasn’t like I was the only person he spoke to before, but now, it felt like I had been singled out and excluded.”

“I started wondering, ’Did someone say something to him about me?’ I became suspicious, overthinking every interaction. And as a teenager, you don’t really understand what’s happening – you’re just confused. I didn’t know what had changed, but I could feel it. And it was painful.”

She tried to put it out of her mind, or focus on other things, but it felt impossible. “My grades dropped drastically. My motivation for school completely disappeared – my drive was gone. Looking back now, I can trace it all, but at the time, I couldn’t make sense of it. I just felt like I was stuck in my own head.”

By the time she was finishing her Kenya Certificate of Secondary Education exams the following year, she felt like she was in a dark place that she would never emerge from.

And then, out of the blue, Mr. Ayiro initiated contact again, just as she was out of school, in early 2007.

“He started sending me texts, friendly messages. It felt nice. I had finished high school at 17, so at this point I’m not yet 18. Suddenly, my friend was back. Finally, after all that time, he was reaching out again. He was calling, messaging, and we were back to our usual chitchat.”

Mr. Ayiro started suggesting they meet and catch up. He had missed her, he said.

“It was never casual meetups like coffee or anything public – we only ever met at his house, which was in the school compound. At the time, that felt easier for me because the school was familiar to me.”

By this time, Evelyne had started calling him Peter.

“We were meeting at his house, even during the school term – sometimes in the evenings while the girls were still in session, and sometimes during the holidays or midterms. I remember feeling like I was sneaking around, but in a way that felt exciting, almost cool. We’d spend whole afternoons together.”

By the time he kissed her, it didn’t feel alarming at all. He was 32, she was 18.

“It felt like a relationship to me. In my mind, when I went to his house, I was going to see my boyfriend – someone who liked me too. That’s how it felt.”

“The way I acted, the way I prepared – those were things you do when you’re seeing someone special. You know, the way you blush, how you shower, how you dress up when you’re going to meet someone who means something to you in that way – that’s what it felt like.”

She once asked him why he had iced her out in third form.

“He just brushed it off – he didn’t give me a real answer…But for me, it was something I struggled with for years. I doubt he even remembers it or understands the impact of what he did. ”

But it wasn’t just her who had experienced that. Several former students described a sense of psychological whiplash around Mr. Ayiro – never knowing if they were in favour or out, or what minor misstep might change the dynamic.

One student (class of 2020) describes a pattern that would make girls feel uniquely chosen, then abruptly withdrawing.

In this student’s recollection, he would make it obvious who his favourites were, even praising girls openly during C.U. meetings: “Maybe in chapel, he’d point at someone and say, ‘You see so-and-so,’ and then proceed to tell a story about how amazing that girl is in front of everyone.”

But the very next day, he might ignore the same girl completely, even “he’d say hi to each and every one of your friends – except you.” The result was a quiet confusion that this student describes as having a pendulum effect, which inevitably makes girls “pine”. “The unpredictability lends itself to teenage girls clamouring to gain his favour,” says this former student.

***

Rev. Marion Strain arrived at Alliance Girls High School in 2006. She was a Presbyterian minister, and would serve as the school’s chaplain for five years. As chaplain, she had a particular connection with the school’s history and heritage. Alliance Girls, just like the boys’ school across the valley, had been started by a trio of Protestant missions; the ‘alliance’ here was between the Methodist, Anglican and Presbyterian missions.

Even so, because the Presbyterian Church of East Africa, P.C.E.A. (then known as the Church of Scotland) granted the land in Thogoto upon which both schools stand – in 1948 for the girls’ school, and in 1926 for the boys’ school – the P.C.E.A has remained the sponsor of both Alliances to-date.

Rev. Strain thus arrived in a school context where Sunday chapel service was mostly along the liturgical lines of the P.C.E.A., but peppered with the influence of the upbeat, charismatic, revivalist style of Kenyan high schools. The school’s C.U. met on Saturday evenings and Sunday afternoons, where that revivalist, evangelical and Pentecostalist streak was more even firmly established and clearly expressed.

These two faith traditions were not necessarily in tension at the school – the school chaplain and the C.U. patrons mostly worked together as collaborators in the spiritual formation of the girls and in the Christian culture at the school.

But in Rev. Strain’s time, she describes her working relationship with Peter Ayiro as “anything but positive”. He was the co-patron of the C.U. at the time.

This was not just due to doctrinal differences, although that did play a big part, she says, as she represented the more conservative P.C.E.A. background and he, from an evangelical one.

“I found him arrogant, aggressive, and condescending – as though he believed he knew more than those of us formally trained in ministry,” she says.

But there was more to their conflict. She alleges that she “personally witnessed the inappropriate closeness Peter had with some of the girls.”

“It was evident almost immediately after I arrived at Alliance. I sent word through the [other] C.U. patron that Peter was not to be involved in any committees or have any patronage over the C.U. I also confronted him directly and told him to stay away from the girls.”

In her recollection, he didn’t take it well, and didn’t like being told to keep his distance from the girls. “So, being an American, but trying the Kenyan way, I decided to get the message to him indirectly.”

Rev. Strain told two teachers to let him know, again, to stay away from the girls. “One morning, right after school assembly, he barged into my office, furious,” she recalls. “He said I had no business sending people to tell him how to behave.”

Peter Ayiro denies that Rev. Strain ever confronted him directly; only that he was told by a trusted senior colleague that the chaplain was making serious allegations about him, and that he needed to be aware that Rev. Strain was watching him. In his account, the colleague told him that Rev. Strain was “trying to fix” him.

“I do remember speaking to Mrs. Kamwilu, one of the principals, about him,” Rev. Strain recalls, adding that he seemed to have a very close relationship with the two principals during her tenure; Mrs. Mbugua and Mrs. Kamwilu.

Both former principals declined to comment on this story, on the allegations raised here.

“At one point, I even threatened to report him to the Teachers Service Commission,” recalls Rev. Strain. “I didn’t follow through – at the time, I thought the threat alone might be enough. And to be fair, after that, he kept his distance from me. I think he knew I wasn’t going to tolerate his nonsense and that I was serious.”

Rev. Strain said she specifically told the C.U. student leaders that she didn’t want to see him near any one of them, at all.

“When I first arrived at Alliance Girls in 2006, I noticed almost immediately the unusually close relationship Peter had with two girls who were leaders in the C.U. Every time I saw them, I saw him. One day, as I was walking into my office, I spotted the three of them in the inner reception area – laughing, giggling, enjoying each other’s company.” This was a section of the main administration block that was typically out-of-bounds for students.

She called the two girls into her office right then, and Mr. Ayiro walked away. She recalls telling them, bluntly, that she didn’t want to see them fraternising with a male teacher – ”especially not him” – because she believed the dynamic was inappropriate.

“They were upset. I told them I didn’t care how angry or irritated they got. ’You don’t know it yet, but I’m protecting you,’ I said. ’And if you continue this, I will make things very difficult for you.’ I took it as my responsibility to protect the girls…because boarding school is already a vulnerable environment. Girls away from home need protection.”

Rev. Strain says she struggled to understand why senior staff did not seem concerned. “It was as if they brushed everything off, like ‘That’s just Peter,”’ she recalls.

The chaplain’s concerns, though sharply expressed, speak to a broader pattern of permissiveness at Alliance – where boundaries between teachers and students were seemingly blurred, and attempts to enforce professional standards were quietly resisted.

Her warnings about Mr. Ayiro were not isolated. Several former teachers interviewed spoke of wider unease among some faculty members about a culture that privileged the teacher’s charisma over accountability, over protection for the students.

***

Ivy’s first impression of Mr. Ayiro was from the C.U. context. She already considered herself a Christian at this point, “because I came from a Christian home.”

But when Mr. Ayiro spoke, she recalls, it was different.

“He was kind of the first person who preached and made me feel the word of God come alive,” she says. “That was my impression of him: That he was very spiritual, very morally grounded, very in tune with God.”

She also says that he projected this aura of superiority – like he was at Alliance Girls by choice, by destiny, and in service to the girls and the school community.

“It’s like he had made this great sacrifice to teach us. I remember that distinctly. As a teenage girl, I just accepted that narrative as fact. And I felt grateful – that this great man had chosen to spend time with us.”

By this time in the early 2010s, Rev. Marion Strain had left the school, and Mr. Ayiro was now the C.U. patron.

“Within C.U., there was actually a smaller group of people he interacted with one-on-one,” Ivy recalls. “So there was the bigger C.U. community, and then there was an inner circle.”

Ivy doesn’t exactly remember how she joined that inner circle, but it happened somewhere between Form 3 and 4. “When I started getting more involved in C.U. and hanging out… with some other classmates who were into C.U., I found that they were already in his inner circle – and I was just kind of welcomed in,” she recalls.

“And then Mr. Ayiro paid particular attention to me very quickly, very easily, for no reason I could point to.”

She recalls that at the time, it was “common and normal” for Mr. Ayiro to show “casual physical affection – not just with me, but with all of us in the inner circle.” She describes him hugging the girls, “right outside the chapel, before or after C.U.”

“He’d hug us, and keep his hand around our waists. Other teachers didn’t do that. But with him, it was common and normal.”

Ivy says that being in the inner circle came with certain privileges, like being called out of class during prep to eat snacks and junk food in the staff room – a huge privilege in a school where outside food and snacks was prohibited for the students.

“We’d get very nice things to eat, out of nowhere – sausages, mandazis, tea. Sometimes we could even take them back to our dorms. Once he brought me a milkshake from Java. You can imagine how it looked to the other girls – us walking into the dorm with things that were illegal,” she recalls.

How did they ‘get away’ with it?

“In that inner circle, almost everyone was a prefect,” Ivy recalls, meaning that the prefects themselves were the ones breaking the school rules with Mr. Ayiro’s apparent sanction.

Ivy said she welcomed the special treatment; she didn’t think there was anything to be concerned about.

“I welcomed it – you know, [first of all] I didn’t understand why it was happening. I thought it was some kind of credit to me. But also, within that was the assumption that he was good and well-meaning. So I wasn’t worried.”

Until one Saturday evening, when he was walking her back to the dorms after C.U. meeting. It was dark, and after 8 p.m.

“I wouldn't have said [that area around the dorms] was particularly private, but I guess it was private enough.” When he was saying goodbye to her, there was the customary hug – but then it escalated, she says.

“This time, when he pulled away, he gave me a quick peck on the lips – and then just walked away, like he was never there. This was in third term, close to KCSE, and I was very shocked. I couldn't believe that everything people had been warning me about was actually true.” He was 39, and she was 17 at this point.

Ivy recalls a situation prior when a female teacher had pulled her aside.

“[That teacher] told me, ‘I've seen the way you and Mr. Ayiro are, and it's not good. You know, that man has a girl like this every year.’ And when she told me that, I just thought, Ah, this old lady doesn't know what she's talking about. I completely dismissed her concerns at the time.”

Ivy says that kiss on the lips is where “everything changed” for her – she was shocked, but also felt implicated in it somehow.

“Even though I didn’t initiate it, even though I didn’t return it, it still happened on my watch. I remember thinking, How did no one see that? We were literally outside. After that, we never addressed it. It was like it never happened.”

The next time she saw him, “Everything was back to normal – as if I had made it up in my head,” she says.

Ivy describes that time being one of confusion.

“I remember thinking – Okay, well, if out of all these girls he's chosen me, maybe there's something here. Honestly, it's embarrassing to think about now, but that's how I thought.”

“Because I was about to finish school – KCSE was just weeks away – [I thought] maybe then we could see. I wasn’t the kind of person to carry on with an affair on school grounds. But that’s where my thoughts were going,” she recalls.

“At the same time, I was thinking: But he's so much older than me. Confusion would be the right word.”

Ultimately, she didn’t confront him about it, because, in her mind, the whole thing felt too big to handle, too transgressive.

“I didn’t bring it up because I wasn’t ready to deal with his answer either way. Also, the timing – I was trying to focus on my exams. I felt that whatever was happening was a little too mature; I was confronted with my own childishness, like I was out of my depth.”

Peter Ayiro denies these allegations, saying he has “zero recollection” of these events.

IV.

Mercy* reported to school in Form 1 in 2011, a few weeks after most of her classmates had already joined, and after other girls had already started friendships and paired up as deskmates and the like.

She describes herself as someone who’s generally shy, and doesn’t socialise easily, but it seemed that Mr. Ayiro’s status in the school reached her even before she really met him.

“The impressions I would pick up at random were... that he was a man with a presence. It seemed like he left a huge impact on anyone who interacted with him.”

And what was very clear is that there were two sides to it, she recalls. Alliance Girls has a house mum-daughter system, where a new Form 1 student would be paired up with a Form 2, who’d be their “house mum”, an older girl in the same dorm who would help the new student into boarding school, be their first friend and look out for them.

“I remember my house mum at the time; she and Mr. Ayiro were really good friends. She would always say all manner of good things about him, about what an amazing man he was. It wasn’t just her – anyone who liked him, really liked him.”

“And then there was the other side – people who really didn’t like Mr. Ayiro. So any time his name came up, it would always trigger strong emotions, depending on where you stood.”

She remembers that at some point in Form 2, she started interacting with him more, and it was casual encounters, friendly talk that became a routine that she would look forward to.

“We’d chat a little – he’d ask about how I was doing – and he would say very impactful things about life, about building character. I really won’t lie: he built my character in some ways,” she recalls, describing him as a “sounding board”, someone who always had something profound to say that would lift her spirits immediately.

In her recollection, she wouldn’t say that they were very close, but then she remembers a sudden fracture in that relationship. He didn’t seem excited to see her, and she started to worry that she was no longer important to him.

“I remember hurting so much, but I couldn’t even explain it to myself,” she recalls. “I had no legitimate ‘reason’ to be hurt, so I just ‘died’ with my own heartbreak silently. you know when people describe heartbreak and say you can physically feel pain? I felt physical pain. And I couldn’t understand it.”

Then, randomly, one day they bumped into each other again in the corridors. He was back to his usual friendly, warm nature. That encounter quickly restored the routine – and then he started calling her his “wife”. He wasn’t married at the time.

That label allegedly came from him, she says, adding, “I just kind of shrugged it off at the time – as long as I wasn't in trouble, I let it be.”

But being his “wife” apparently came with privileges, she says, recalling one incident where a few students were in trouble and were made to clean the dining hall as punishment. Mr. Ayiro apparently wanted to punish them further, and had told them to meet him at the assembly point for their next instructions.

“But by then, a few people had caught on. So, the girls who were being punished asked me, ‘Please go speak to Mr. Ayiro. We've already cleaned the dining hall for hours. Maybe he’ll listen to you.’”

Mercy says she went and asked him what the plan was.

“I said to him, ‘I think they’ve already learned their lesson.’ He gave them a little lecture – and then he told them, ‘But you know what? Wife has said you’ve had enough punishment. So you are dismissed.’ He actually said it like that – ’Wife has said’.”

Mercy also recalls that he asked her if she wanted to go for a trip to Nyeri for the drama festivals, even though she wasn’t part of the drama club. Of course, like any boarding school student, any trip out of school was a huge privilege, and she immediately said yes. “I just separated it in my mind: Yeah, I’m ‘wifey,’ so I guess I get to go for drama trips even when I don't need to.”

Mercy acknowledges that through this time, several teachers warned the girls not to hang around Mr. Ayiro. And she remembers something else: “There was one time an old girl walked past us without even saying hi, and I remember Mr. Ayiro made a comment: ‘You know, out there, the old girls don’t like me’.”

When Mercy asked why, she recalls him saying something like, “‘There are stories that go on about me,’ and then he moved on quickly, like he didn’t want to stay on the topic.”

In February 2015, Mercy returned to the school to pick up her KCSE certificate; she had just done her final exams the previous November. That day, she bumped into Mr. Ayiro at the school hall – he was running a Drama Club practice over lunch hour. The hall is centrally located in the school, in front of the assembly area and right opposite the classroom block.

“Of course, I was so excited to see him – he had been such a huge part of my high school life. He told me to wait for him as he wrapped up the practice, so I did.”

It was around 2pm., the bell rang, and the girls went back to class for their afternoon lessons. “And right then – before I knew it – this man was kissing me,” she recalls.

“If anyone had come back for their water bottle or forgotten something in the hall, they would have caught us there. He kissed me, and… in the process he asked, ‘Should I stop?’”

Mercy says she told him to stop, and he did. “I told him bye, and I went home. And that was my last interaction with Mr. Ayiro.” He was 40, and she had just turned 18 that month.

What struck her about that day, is what she describes as “the casualness, the recklessness” of that sudden kiss, in broad daylight, in the middle of the school compound.

“But it was also everything else that had been building up. The rumors I’d heard all through high school – whispers, warnings, stories that no one ever directly confirmed.” Mercy only told one friend about this incident, her year-mate Karwitha Kirimi, whom I’ve spoken to and has corroborated Mercy’s account in this story.

Peter Ayiro has denied ever initiating physical or sexual relationships with former students of Alliance Girls soon after they leave the school.

***

Cecilia* describes herself as a somewhat quiet student, “I was not a loner, but not very social either. Just somewhere in between. I had a few friends, and I kind of kept to myself. That was my vibe.”

She says that she did enjoy high school. It was a new phase – becoming a teenager, finding new friends. There was something exciting about stepping out of childhood like that.

She remembers Mr Ayiro as being friendly and approachable, as someone who could hold a conversation with the girls beyond just academics. You couldn’t say that about all the teachers in Bush – many of them were stern and distant.

She also remembers something that used to happen in between classes or in between sections of the day – he’d stand outside his office at the German department, and “there would be this group of girls stopping to say hi, getting a hug. It became a thing. He’d stand there, and girls would run over, just to get a side hug. He used to squeeze people really tight.”

But in that context, because it was so normal, it wasn’t a big deal – just a quirk that would make some of the girls laugh. Those kinds of hugs seemed like just part of his jovial personality, she recalls.

Cecilia says she didn’t think much of it. Until one day, when the girls were having a movie night in the school hall. What happened next is based on her recollection.

It was dark, almost 8pm and the movie was about to start. She was standing outside the hall having some chit-chat with Mr. Ayiro. She was about to say goodbye and join her friends inside the hall, when he reached over and gave that familiar side hug. But this time, she felt his hand had touched her breast, from the side.

“Initially, I thought, ‘okay, what is happening?’ But then I went and watched the movie, and I never thought much about it… I guess I rationalised it, that this is because he was so used to hugging people. Now, that’s the thing. Like, he really was into hugging his students. I thought maybe he hugged me and his hand slipped.”

She ignored it, she says, and continued to be friends with him. The next time it happened, his hand apparently slipped again. But this time, “he told me that I have really nice boobs.” He verbalised it. He was almost 40, and she was 17.

A few weeks later, he was the teacher on duty, which meant that he stayed around the classes until after 10pm, until the girls were done with prep and heading back to the dorms. On this particular day, she remembers that she was on her way to the dorms when he called her over to the German department. He had switched off the lights and was preparing to lock up, she recalls.

“He called me into the department, and then he put his hands under my shirt, and started touching me. His hands were caressing my boobs, under my bra. At that point, he got a hard-on, and he asked me to feel it. I was thinking that this whole situation is wrong. But I couldn’t stop it right in that moment because, you know, this is somebody who’s older than you, and at the back of my mind I still respect him.”

She went to the dorms, trying to understand what had just happened. The next day she told her best friend about what had happened the previous evening. “She was mad, really mad. She just told me to stay away from him.”

This was 2014, it was already the third term of Form 4, and they were deep in KCSE preparations, and there was so much going on. “There wasn’t anyone we could talk to – no female teacher who felt safe enough. And with him being the principal’s favourite, and with other teachers either hating him or fearing him, it felt like there was nowhere to go. So I just told her, ‘Don’t tell anyone. Let’s just finish school.’”

Peter Ayiro denies the allegations outlined in this account.

Through these last final weeks of the term, after that incident at the German department, Cecilia says that Mr. Ayiro acted “completely normal” towards her. He even asked for her number as she was doing her last exams and clearing out from the school, and she gave it to him. Everyone was exchanging contacts at the time and promising to stay in touch.

“Honestly, I wish I had reported it. Not just told my friend…I wish I had been more vocal. But at that age, I was young. I was naive. I didn’t fully understand what had happened …or how serious it was. And I was afraid. This was someone I respected, someone I feared. I didn’t want him to hate me, or to retaliate somehow.”

Because he had her number, she says Mr. Ayiro kept reaching out to her the following year, asking her when she’d be free, when she’d next be around the school, or when she could come over to his house.

“I always avoided the question. I’d tell him I was in campus; that I was busy. I had moved to Nakuru for university…I’d say, ‘I’m not in town,’ and that was that. That was 2015 – he really, really tried to have an audience with me, but I kept avoiding him. I just didn’t want to go there.”

A couple of years after their Form 4 exams, Cecilia met up with a few of her former classmates. They were a little older now, and had seen a bit more of the world. They were catching up, sharing “about how crazy high school was, especially in hindsight,” says Mwende Mukwanyaga, one of the girls at that meet-up.

“We began unpacking how, back then, we were in situations that we didn’t fully understand weren’t okay. But growing older made us realise – no, that was actually messed up. It wasn’t okay…There was real power play involved. I think that was the moment we were starting to understand what power dynamics really mean.”

It was at this meeting that Cecilia first told her former classmates what had happened between her and Mr. Ayiro.

“She opened up and said it was much deeper than we thought… that it wasn’t just friendship or favouritism,” Mwende recalls. Karwitha Kirimi was at that meet-up too, and Karwitha knew about Mercy’s account back in 2015. They realised they all had different fragments of what seemed to be a bigger pattern.

By 2019, Mwende was less in touch with Cecilia, but what she had heard weighed on her heavily. Mwende decided she’d host an old girls session – maybe even start a regular “Big Sisters club” in the school, where they could talk to the current students about power, consent, teacher-student relationships, and how to recognise you were being groomed.

Mwende started a WhatsApp group which she titled “Bush SOS” with former students that she thought would be interested in supporting the initiative – this writer included – and then went to see one of her teachers who was still at the school, whom she thought would support the idea.

Her talk with that teacher did not go as expected.

“The teacher said they didn’t want to create trouble with the admin. That was the phrase – they don’t want trouble with the admin.” The teacher in question, who wishes to remain anonymous, has corroborated this account. “Actually, most of the things to do with the old girls were organised by Mr. Ayiro. We tried to keep off anything touching on them, because he kind of dominated it; it was seemingly his thing,” this teacher says, adding that she didn’t want to step on his toes by being seen to endorse and engage this Big Sister’s club.

The session ended up being a talk with just the Form 3s, and for a single afternoon, with instructions to frame it as a more general session on life skills, careful broaching on sex and consent, and not to be too explicit on the grooming angle.

Mwende reflects on that “failed initiative” now.

“The way the teachers ended up framing the session was like, ‘Oh, the Form 3s are a bit problematic, and they need some guidance from old girls.’”

In that moment, Mwende says, it hit her – the adults in the room “were failing, and [they’ve] chosen to continue failing...because this is the bystander effect.”

Today, she remembers how the teachers claimed not to have evidence to act, but she wonders how they expected a teenage girl to take on a risk that they weren’t willing to take themselves.

That group only came to the school once, in July 2019. Their WhatsApp group was quietly abandoned soon after the Covid-19 pandemic hit the following year.

***

Ruth* was in Form 4 when that old girls group came in 2019, so she missed that session since it ended up being only for the Form 3s. She remembers Mr. Ayiro as a teacher she held in very high regard. She respected him and saw him as her spiritual authority, as she was very active in the C.U.

She wasn’t as close to him as some other girls in her year; she wasn’t one of the ones who was constantly milling around him. She didn’t really consider herself to be in his ‘inner circle’, but she interacted with him all the same – he was warm and approachable, “you could have conversations with him that extended beyond academics, and being around him felt like a slice of home away from school. It was that kind of connection.”

After leaving high school in November 2019, her parents gave her a phone to use as her own, and she started sending out daily Bible verses to her contact list. It was just a way to keep in touch with friends, and maybe make someone’s day. Mr. Ayiro was part of that contact list, and usually he’d text back with a simple – “thank you”.

But one day in April 2020, what he texted back threw her off a little. She recalls his message that said something along the lines of, ‘Thank you for this. I actually miss you.’”

“I found it a bit perplexing, considering we weren't super close. So, I asked him, ‘What is it that you've missed?’”

He replied, saying that there was this particular day in high school when she had said hello to him, and it felt like he wanted more, like there was an electrifying connection between them. He mentioned that this happened while she was still in school.

“Now, my mind was racing, trying to piece everything together. Was this the same Peter Ayiro from C.U?… There was all this stuff going on in my mind. I started thinking about why this was different… I was confused, to be honest.”

At this point, his friendliness didn't strike her as alarming, or at least not yet.

“However, at this point there was this one incident at school that I remembered in that moment,” she recalls. “I was switching off the lights in the chapel, and he came over to help. He seemed to lean in and tried to kiss my forehead. It took me by surprise, and I instinctively backed away. I guess he got the message that I wasn't comfortable with it.”

She adds that there were “probably about four or five occasions” when he would hug me or greet her in school “in ways that felt quite intimate or inviting.”

“His hands were certainly just above my bum and then it would be quite tight, quite inviting and suggestive. There was also the handshake – I don't know if you know the handshake that guys sometimes do, scratching your palm in the process. He did that in school a couple of times.”

Peter Ayiro has denied ever interacting with any student in a way that was intimate, suggestive or emotionally entangling.

Back to the text exchange in 2020. Ruth recalls that that day, he began telling her how he misses her, and he started sharing stories about himself. By the time the evening ended, he had told her a lot of things that he had done in his life – his sexual encounters, or “escapades” as he called them.

Ruth says the texting marathon had started at around 1pm and it went on until after 10pm. She remembers thinking it was the longest conversation she’d ever had with him. He was 45 and now married; she was 18.

Ruth struggled to make sense of what had just happened.

“Everyone knew him in a different light, and here I was, being introduced to another side of his personality. Was this really the same C.U. patron from high school? I mean, I thought to myself, my friends would never believe I was having these conversations with the same person. He had an image, a devout and God-fearing one, and even in some way I felt that he had a connection with God himself. There was this whole level of respect and aura surrounding him.”

The texting continued over the next few weeks, until mid-May when he asked to meet her in person, she recalls. This was during one of the lockdowns of the Covid-19 pandemic. Ruth agreed for them to meet up at Karura Forest and go for a walk.

“Part of my reason for meeting him in person was to confirm that it was indeed him sending me the texts because, you know, during school days, some other male teachers were quite forward about their intentions. For a moment, I even thought that maybe I had mistakenly saved some other teacher on my phone under his name.”

***

In the years since leaving Alliance Girls, some alumni have spoken out about inappropriate relationships between teachers and students during their time at the school.

In one instance, a former student from the mid-2010s publicly shared on an alumni Facebook group in 2018 that she had become pregnant in Form 4 while still in school following a sexual relationship with a teacher. She named the teacher directly in the post, identifying herself and calling for accountability; by then, her son was around five years old. This account was corroborated by several of her classmates.

According to what she posted, the teacher had left Alliance only after her parents intervened, but by that point she had already done her KCSE. In the alumni discussions that followed, other teachers were also mentioned as having behaved inappropriately or having crossed boundaries, but the name that has come up most consistently – and over the longest stretch of time – is Mr. Ayiro’s.

His patronage of the C.U. where he advocated for values like purity and integrity, and his continued presence at the school even as others moved on or were quietly removed, is part of what makes his case so distinct.

***

Ruth says that on the agreed day, he picked her up from her parent’s home in his car. When she saw him, she says, “that’s when it first hit me that it had been him [texting] all along – that it was really him.”

They got to Karura and started the walk, and Ruth remembers being very tense, feeling like her heart was racing and she couldn’t breathe. Later that afternoon, they got back to his car, and she recalls that was the beginning of their sexual encounters. It started right there in the car.

“After that meetup, I returned home feeling incredibly confused. I was holding it together until I left his car and entered the house, and then the events of that day hit me. I was in a total mess. I said a prayer, then proceeded to delete every message we had exchanged. I messaged him, telling him that I couldn’t continue with this.”

But he reached out again a few days later, and persuaded her to meet him. She reluctantly agreed to meet him at a café, but when he picked her up, instead of taking her to the café, he started driving in an unfamiliar direction.

“My mind started racing, thinking of all sorts of crazy scenarios. He noticed my anxiety and said, ‘Just relax, just relax.’”

After a few minutes, she started to realise they were heading in the direction of Alliance Girls. He asked her to move to the back seat of the car as they neared the school. Ruth interpreted this as a move to avoid attention from guards at the gate.

They got into his house. At the school, the teachers quarters are at the periphery of the school compound, so the drive to his house would have involved a sharp left turn at the gate instead of going straight ahead on the driveway to the main administration and classroom block. There would be hedges on either side, of cypress, kayaba and duranta, but the teachers' houses typically did not have any gates or tall fences.

His was House #30, a squat one-bedroomed bungalow that shared one porch area with an identical bungalow next to it. These were the bachelors’ quarters of the school reserved for the unmarried teachers, but even after his wedding in 2018, Mr. Ayiro maintained this house at the school, though by several accounts his wife didn’t usually live here with him.

“Things started to get intense. I went along with what he suggested because, well, I was a bit naive; I had never been with a man before, not even a boy my own age.”

She met him multiple times after that – Ruth recalls that save for the Karura one, each sexual encounter was at his on-campus residence, at Alliance Girls. She tried to break up with him many times, but she found herself being drawn back in. She remembers feeling incredibly alone.

“I kept asking myself, ‘How on earth is this happening, and how should I handle it?’ Sharing this with someone who had been under his influence or spiritual guidance could potentially shatter their faith. Despite being the target here, I felt a tremendous weight of responsibility. I was struggling with the internal conflict of it all.”

Peter was asked to confirm or deny this account, of having a sexual relationship with an ex-student that started with a walk at Karura Forest in 2020. He did not comment by the time we were publishing this story.

V.

After high school, a number of former students—including those who had once been discipled by Mr. Ayiro while at Alliance Girls—began attending his church, Kingdom Life Centre (KLC), where his father, Pastor Aggrey Ayiro, served as senior pastor.

Some congregants had been with the Ayiro family since their days in the Chrisco church, while others had joined more recently. Since KLC’s founding in 2003, there had always been a small but steady presence of ex-Busherians in the congregation.

Ruth says she had come to KLC during this season, to make sense of what was happening in her life.

“I joined his church during that season in an attempt to better understand what they were preaching, and how he could be two different people in one. But it didn't provide much clarity. Attending his church didn't help me engage with him on a spiritual level either. Maybe we had crossed lines that were hard to uncross.”

Ruth remembers going through a period of intense turmoil, with tears and questions directed towards God. She confided in one youth group leader, who also happened to be an ex-student of the school. This youth group leader, who wishes to remain anonymous, has corroborated Ruth’s account of the nature of her relationship with Peter, and of the emotional and spiritual toll it took on Ruth.

“I don't mean to say that my faith entirely depended on him, but there was a growing conflict over time.” Ruth wondered whether she could continue believing in God, even as she tried to separate the gospel that she knew and the messenger was revealing a different side of himself.

“It became increasingly tricky, and I found myself losing my grip on the message and my faith in God. I was grappling with so much confusion. But eventually, in August of that year, I made a choice. I stopped fighting it, I stopped trying to be a Christian in the way I had been.”

Later that year, she remembers meeting up with another ex-Busherian, who was her friend and classmate. She hesitatingly shared what she was going through in her life, and her friend asked her if the man in question was someone she knew.

“I said yes, and after a couple of guesses she asked me if it was Peter. I confirmed it, only for her to surprise me with her own news – that he had been sending her numerous love letters and had expressed a strong desire for a relationship, but she wasn't interested.”

The two girls were angry and confused.

“It was a complicated situation – not only was he married but we realised he was also pursuing both of us. In the end, we decided to block him from both of our lives. Throughout November, we navigated through the confusion and healing process together. I'm thankful that I had her by my side during that time.”

Ruth says that with this girl, nothing physical had happened between her and Peter; they hadn’t even met in person. But in high school, they were really close, she was definitely one of the girls who would have been described as being in his inner circle.

“As we vented our frustrations and talked about our situations, we both felt furious and hurt. It was during those conversations that I decided to cut ties with Peter. I just went silent on him.”

In early 2021, Ruth heard from a former schoolmate who passed along unexpected news: Peter’s wife was starting to make quiet inquiries. Word had reached her through informal channels that there might be troubling stories about her husband’s conduct, and she was looking for confirmation.

Ruth was told by a friend that Peter’s wife wanted to meet her, but she didn’t feel comfortable meeting with Peter’s wife in person. Ruth decided to reach out to her, not to cause scandal, but to answer her questions truthfully.

Ruth created a generic email account to protect her identity. “I wrote to her and said, ‘I am the girl you wanted to talk to about Peter. Feel free to ask any questions,’” Ruth recalls.

“She wrote back and began asking questions. We discussed my interactions with him, and I described everything to her. It was tough at times because it was still fresh and quite overwhelming.”

Then she asked for proof – screenshots, photos and the like, and Ruth says she sent them.

According to Ruth, Peter’s wife was shocked by the information and said she needed time to process. Ruth recalls that she handled the conversation with calmness and maturity, but eventually ceased communication.

“I have to add that she’s so mature and gracious, she didn’t say or do anything to harm me; she was amazing, considering she had no idea. When I confirmed that these events happened after her marriage, she was like, ‘Oh my God.’”

“But she handled it with grace, calmly asking questions, which I answered. She told me she needed to talk to him. After that, I never heard from her again. I became a ghost to both her and Peter.”

Peter’s wife was approached for comment to clarify on this account outlined here. She did not get back to us by the time we were publishing this story.

Peter Ayiro told us in a comment that that season in early 2021 was “dramatic”, and that his wife confronted him about an extramarital affair at this time. She told him she had details and evidence, he says. He says that he admitted the affair, but adds that it had “nothing to do” with any ex-student of Alliance Girls. He adds that he and his wife then escalated this admission of an extramarital affair to his father, Pastor Aggrey Ayiro, together.

VI.

Grooming. Breadcrumbing. Gaslighting. Abuse.

One morning in February 2020, as she was just finishing dropping off her children at school, Priscah Njuguna (neé Matende, class of 2001), received a call from another ex-student, Diana*. They knew each other in high school, as they had both been active members of the C.U.

At the time of this phone call, Diana was a member of KLC, pastored by Peter’s father, Pastor Aggrey Ayiro. Priscah attended another church, Life Reformation Centre (LRC), led by Pastor Joseph Njoroge.

Both these churches were part of a global network of congregations and organisations called Congress WBN, headquartered in Trinidad & Tobago, which you can think of as an overall denomination, though they wouldn’t describe themselves that way. On their website, Congress WBN says it is an organisation whose goal is “faith-based global human development”.

This is the network that Pastor Aggrey had joined after leaving Chrisco in 2003; Pastor Njoroge at LRC was part of Congress WBN’s leadership, as the point person in East Africa.

This network and the relationships between these organisations is important in understanding what happened next.

Diana and Priscah were both in a WhatsApp group of ex-Busherian C.U. members, and in the group were old girls from across two decades, all keeping in touch, praying and encouraging each other, especially during the Covid season.

“[Diana] called me and told me that there was a much younger ex-Busherian in the WhatsApp group, who told her that she had been struggling due to a sexual relationship with Peter.” Priscah knew this girl, she attended LRC and used to see her at church. “I was shocked; this was the last thing I expected to hear on a random morning.”

Two days after that call, Priscah called up the girl to hear the story from her. That girl, Mo, confided in Priscah and Diana – who were both part of her faith community – at length. According to their accounts, she described how, after high school, her interactions with Mr. Ayiro shifted dramatically, with a flurry of texts, phone calls and romantic overtures that left her deeply unsettled.

“She told me that when she was in high school, she was close to Mr. Ayiro; he was the patron of both the drama club and the C.U. and she was active in both. She considered him a mentor at that time. After she graduated high school, his behaviour changed dramatically. He started calling and texting her incessantly and declared his love for her, which kind of threw her off.”

This was the beginning of a sexual relationship, Priscah says, from her recollection of the girl’s confiding in her. In mid-2019, when this relationship began, Peter would have been 44, and this girl just over 18.

After hearing Mo’s story, Priscah and Diana decided to escalate this to the church leadership. Priscah’s idea was to report this to her own pastor, Joseph Njoroge, as the head of the East African chapter of Congress WBN. She believed that she was escalating it to someone who had oversaw the whole network in this region, and could intervene with Pastor Aggrey over at KLC.

“I felt a sense of responsibility, as we belonged to the same church, I thought I should report the incidents to my pastor. I believed that if the church leadership was informed, they could take appropriate action, including having Peter confess to his actions. My immediate concern was to stop him from teaching at Alliance, as I felt that he was in a position where he could continue to exploit others.”

Priscah informed Pastor Njoroge, who gave her a set of instructions, “which we followed to the letter,” she says, including that Mo should let Peter know that she had come forward. Mo reported to Priscah that she tried to get in touch with Peter, but that he had “ghosted” her.

Priscah and Diana describe this season as a turbulent time, with “rumours flying all over”, but they saw no visible action at the time that was addressing the issue of Peter’s apparent pattern of relationships.

Around this time in early 2021, Priscah, Diana, and a few other ex-Busherians – this writer included – were added to yet another WhatsApp group, which one of them titled “AGHS- Delicate Issues”. There were a lot of conversations about what each of them had heard, witnessed and experienced regarding Mr. Ayiro’s conduct, and triangulating what seemed to be a worrying pattern with younger girls. They discussed and had meetings on what could be done – perhaps escalating their concerns to the principal, the school board management, maybe legal action?

“The main issue preventing us from taking legal action was that we didn’t have a primary victim willing to press charges at the time,” recalls Ciru, class of 1992, who was part of that group. “As a third party, we couldn't proceed because anything we would say would be considered hearsay, which is not admissible in court. This was a major setback and ended [that avenue], which was disheartening.”

At this time, Priscah and Diana decided to do what they could: put their concerns in writing to Pastor Njoroge, and try and pursue this through the church structures. The letter they wrote is over 3,500 words long, but in it they outline what they knew so far. The letter, which this writer has seen, begins:

Hello JN,